“I want to kill.” How the famous Hlib and other children of Kherson live a year after their liberation

In addition to traumatic experiences, the biggest problem facing children and adolescents is lack of communication. They mostly experience their fears alone.

Explosions are heard in Kherson day and night: after the de-occupation, the Russian army would not stop its daily shelling. The war has completely changed the lives of the children in the Kherson Oblast; they have survived the horrors of occupation, abductions to Russia, and continuous missile hits. Children study online and hardly ever meet their peers. They can no longer walk safely on the street as they used to. Instead of dreaming of new bicycles or toys, there is a single dream left: never hear the sound of a siren again. Read and watch in the special project “Decoding Ukraine” how the children of Kherson live a year after the liberation.

About 6,000 children are currently living in Kherson. Despite the Russians having left the city, they still hold the children hostage by shelling it with 120-mm mines and Grad rockets coming from the opposite bank of the Dnipro. In the year following the de-occupation, the Russians killed 405 civilians, including 10 children, in the liberated Kherson Oblast. Another 75 minors were injured. But there is one thing that the Russian troops took away from all the children of the Kherson Oblast ― a normal childhood. Russia has turned their everyday life into an endless sprint run from bedrooms to basements.

* * *

“Who are you?” asks Hlib when we call him to arrange a meeting. It’s not safe outside these days, when Kherson celebrates Liberation Day, as Russian troops keep shelling the city centre, so we agree to meet at his family’s place.

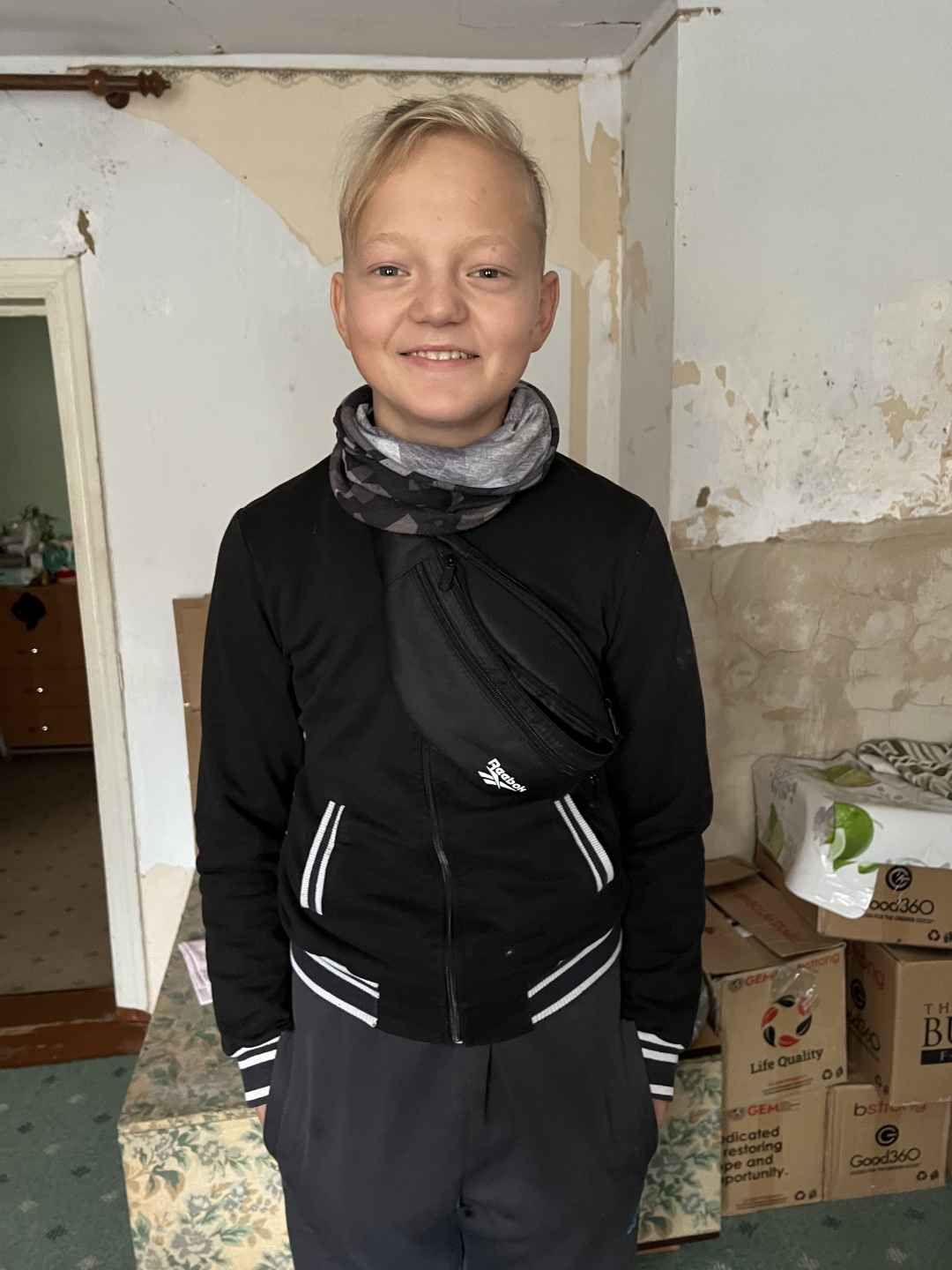

Hlib Sokolov became world-famous after the de-occupation. His photo went viral in the first days of the liberation of the city, becoming a symbol of the childhood stolen by Russia ― it shows a boy with an unchildlike stern look. This face seems to personify everything that the war brought to the Kherson Oblast.

Hlib, 14, lives with his mother Ania and brother Nikita in a small house in Zabalka ― a neighbourhood dominated by private houses that have been damaged by shelling. Ania invites us in and shows us to Hlib’s room. There are almost no new things in the room, and it is clear that the family is living on a tight budget.

A simple laptop sits on the table, which was given as humanitarian aid so that Hlib could study online, and on the shelf, there is a schedule written in child’s hand. Hlib says that he enjoyed going to school much more. Studying online is difficult and boring, and many things remains unclear. The lively teenager obviously misses live communication. Power and Internet outages are not conducive to learning as well. The teacher lives in a neighbourhood that often gets shelled, so she has to interrupt classes regularly.

Like most teenagers who remained in Kherson after the de-occupation, the only way to relax left for Hlib is to roam the streets together with his pals. Hlib has three such pals. He shows me the bike he uses to get around and tells me how he saw an Iskander strike the “White House” ― this is how Hlib calls the office of the Kherson Oblast State Administration on Freedom Square, which has its facade decorated with a large blue and yellow flag over the boarded-up windows these days. Then, with terrifying accuracy, he describes how he came under fire near an ATB store, fell to the ground, called the police, and learned that a passer-by had been killed by shrapnel not far away.

Hlib and his mother have a good-natured argument about the boy often wandering around where he shouldn’t be. The Sokolovs’ house is only a couple of kilometres away from the river, and Hlib would frequently be there while his mother thinks that he’s in the neighbour’s yard. But in general, the family is in high spirits ― Hlib will be leaving for Yaremche soon. The boy has never travelled outside the Kherson Oblast before. This trip is free for Hlib and other children of Kherson, and such trips are organized to take the children out of the danger zone at least for a while. Anna has cut both brothers’ hair in the latest style, and Hlib smiles happily when he talks about his plans for the long-awaited trip.

Yuliia Svyrydova, a psychologist who handles children in Kherson, says that adults are generally unwilling to let their children go. The long months of occupation and the trauma that families have endured make children and parents try to stick together more. Even when being together means staying in an incessantly shelled city. In addition to the traumatic experience, Yuliia mentions the lack of communication as the biggest problem facing children and teenagers. Children don’t go to school, studying online instead, and can’t get together to spend time with their peers because of the constant danger. Therefore, they largely have to overcome their fears alone.

We ask Hlib about his plans for the future. The 14-year-old’s answer is stunning: “I wanted to kill those people who came here.” We feel hard-pressed for words after that, but continue nevertheless. Hlib says that he wanted to be a chef and loves to cook, but the war changed his plans radically, and he wants to become a soldier now. The war changed everything not only for this family, but for everyone here in Kherson.

Russians massively shelled the centre of Kherson on the anniversary of its liberation. Children traumatized by the occupation now live under a daily barrage of fire. It would be hard to imagine a children’s drawing contest or a children’s dance class held in these conditions. So, we set out to see how organizations that provide humanitarian, psychological, and social aid to children in Kherson operate. We are met by Iryna Kostiniuk from the volunteer organization United by Love for Children. Iryna used to be a fashion designer, but the war changed her life dramatically. She now dedicates her entire life to volunteer work.

In the hallway, we see brightly-coloured children’s drawings, and Iryna explains that they are brought by those who come to receive humanitarian aid, the so-called “hygiene pack” ― a large box with all the essentials that should last them for a month. Clothes, footwear, and sweets are also distributed. During the interview, Iryna cannot hold back her tears: “There are children who witnessed their parents being tortured. Their parents were beaten in front of them, mothers were tortured… It’s very scary. It’s hard for everyone.”

Humanitarian aid is not the only reason why families with children come to the centre. The main thing is communication and the opportunity to escape the terrible everyday life for a while. Since children do not go to kindergartens or schools, they miss socializing sorely, and the UNICEF children’s room becomes a magnet that attracts with its cheerful laughter and music. There are classes in art therapy, sand animation, and just the opportunity to play with peers. Parents are not allowed to leave for security reasons, and most of them wait right there in the hallway.

We start a conversation with Iryna, who brought her five-year-old Sasha to the classes and is waiting for him with her husband. There is a mixture of joy and excitement on her face. Iryna says that they first came for humanitarian aid, but when Sasha heard the laughter and music, there was no stopping him. The family lives in the Korabelnyi District, the city’s most dangerous neighbourhood. They hide in the basement only when the shells land too close. Concealing her fears is the hardest thing for her.When asked if she is having a hard time, she answers. “I’m not allowed to cry; I’m not allowed to show that I’m scared because I have a child and parents.”

However, only a few of the more than 6,000 children who still remain in the city make it to the children’s room. Some are reluctant to move around the city once again, while others, such as Zina’s family, organize leisure activities for their children at home or cooperate with neighbours.

Zina and Oleksii have two sons: Andrii, the eldest, is ten, and Kostia, the youngest, is six. We met them on the train from Kyiv to Kherson; they were coming back from Kyiv, where Zina takes her children from time to time to “relax.” This time they were taking the eldest to see the doctors. Zina, her mother-in-law and the boys lived in Kherson throughout the occupation, then Oleksii joined them after the liberation, and they decided to stay. For a year now, the family has been living under continuous Russian shelling. Zina says that sometimes it gets hard, but she emphasizes all the time that it is much harder for our boys and girls out there at the front; therefore, one should not complain and give up even when it gets very difficult: “The shelling indeed never stops, but we are free. Life goes on, we are free. It is impossible to put into words what we felt back then.”

We talk to the boys in the brightly lit and freshly renovated children’s room with a brand-new bunk bed in it. The brothers are allowed to stay there during the day only when there is no heavy shelling. The family sleeps in a room where the rule of two walls works. Andrii is a fourth grader, while Kostia is still in kindergarten, and both study online. Andrii says that most of his friends have left the city and that he misses the time when they all would get together. The boy says he would like his friends to come back, but even if they do, it will not be possible for them to go out “normally” yet because of the shelling and constant anxiety.

The family sadly recalls their free time spent on the banks of the Dnipro, the left bank, where they would walk in the forest on weekends. They would have to travel much farther now. Everyone we talk to misses the Dnipro because it’s hard to live in a city on the river that is the main source of danger. In Kherson, even the districts are ranked according to their distance from the Dnipro as more or less safe. Tavriiskyi is a relatively safe one.

We go to Café 11/11 in the Tavriiskyi neighbourhood. The café decided to celebrate the liberation day with free coffee, so there are a lot of patrons outside. The proprietor Oleksii says that he opened the café in the summer because he had long wanted to do something like this in the city. When asked if he is not afraid of investing in something that can be destroyed at any time, he says, “People here are like ants, rebuilding brick by brick.”

In the Tavriiskyi neighbourhood, we also meet eleventh-grader Mykola who has wrapped himself in a flag and walks near the Pyramid shopping mall. We ask him about his leisure time and school, and he says that he continues to study, but many people have “let it go” because the lessons are held online, where no one controls you and never asks why you’re not there. We talk a bit about Mykola’s life in the city and what has changed. The teenager bitterly replies that his friends can no longer get together and walk along the river: “It was a terrible summer; it wasn’t the same summer as before the war, it wasn’t the same at all…” Tears involuntarily come to the boy’s eyes.

Maria Avdeeva, Artem Lysak

Hlib Sokolov in the header photo. Photo collage by Artem Lysak