Ukrainians in Russia: When, how and why did largest Ukrainian diaspora disappear from view?

Or what one Zelensky decree means for the life of the Ukrainian diaspora in Russia

The Decree on "Historically inhabited by Ukrainians territories of the Russian Federation" signed by President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelensky on the day of Unity of Ukraine, January 22, 2024, is still being discussed on professional platforms and in social media. And here we can fully agree with the opinion of Askold Lozynsky, a lawyer and longtime head of the Ukrainian World Congress (UWC, the coordinating organization of all Ukrainian diasporas in the world), that the authorities have only now turned their attention to Ukrainians living in Russia. In fact, the urgency of such a legislative initiative is 15 years overdue.

Another controversial issue is the absence of some territories densely populated by ethnic Ukrainians among those listed in the decree: in particular, the so-called Green Wedge in the Far East. And another, no less complicated question is whether it is realistic to return Ukrainians who wish to do so to their homeland at this time of war and closed borders.

In any case, there is a common vision that the full-scale invasion has changed the optics of the Ukrainian authorities towards fellow citizens who found themselves "on our land, not theirs" (Taras Shevchenko).

Would such a decree have appeared without the full-scale invasion? This is a rhetorical question, but it is also important for understanding the changes in Ukraine's geopolitical approaches and the rapidity of these changes. But first things first...

How many and where do Ukrainians live in Russia?

The history of Ukrainians and their settlement and even colonization of Russian territories is linked to many political and historical factors. For example, the borders of Ukraine, which were defined in 1917 and later, did not fully take into account the ethnic component during the Soviet era. Historical channels, such as History for Adults here and Taras Shevchenko here, will help us understand the historical causes and preconditions of Ukrainian migrations and the territorial boundaries of the metropolis and colony.

We will record some important data from open sources that will allow us to understand more about how the largest diaspora of Ukrainians turned into a virtually invisible one. There is still no consensus on the number of Ukrainians living in the Russian Federation. Figures range from 10 million (Askold Lozynsky), approximately 5 million (Alexander Alfyorov) to 1.1 million (based on the 2010 Russian census). It is important to note here that this data cannot be confirmed or denied, as we have not had any research on this topic since 2014. Unfortunately.

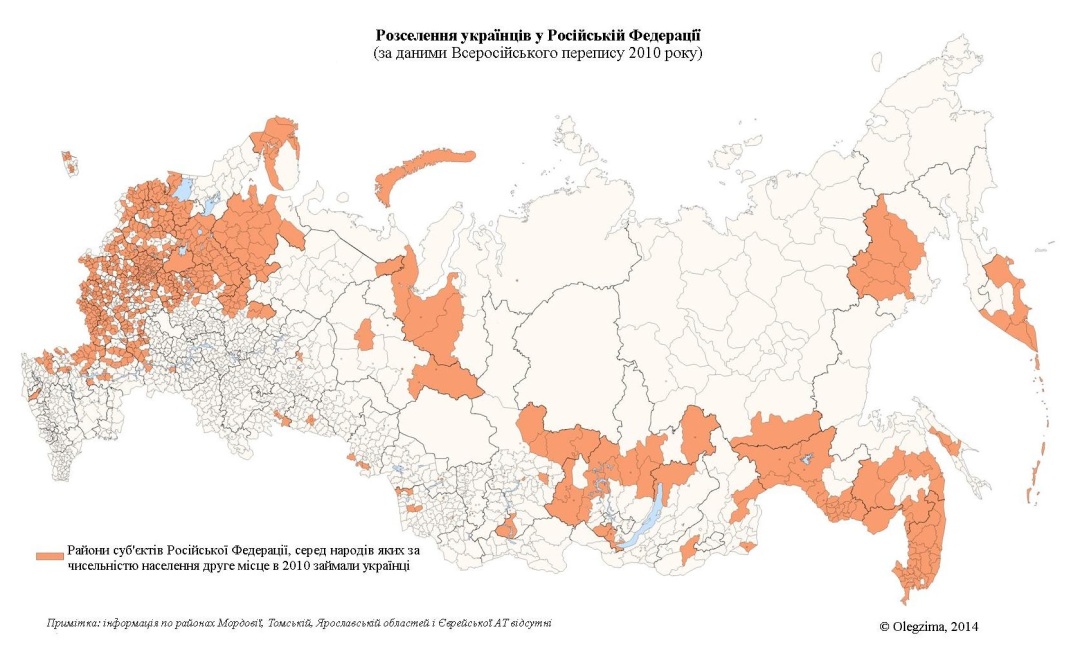

The most numerous Ukrainian communities were in Moscow, St. Petersburg, as well as autochthonous settlements in the areas of Kursk, Voronezh, Saratov, Samara, Astrakhan, Vladivostok, Kuban (Krasnodar Territory), Don, from Orenburg to the Pacific Ocean, and in the same area called by Ukrainians the Green Wedge, the southern part of the Far East with important cities such as Khabarovsk, Vladivostok, Komsomolsk-on-Amur, and Ussuriysk. It is home to the descendants of Ukrainians who were resettled more than 100 years ago 10,000 kilometers from their homeland as part of Stolypin's reforms.

In general, the Ukrainian diaspora in Russia is (or was) the largest of the Ukrainian diasporas in the world. Based on 2010 census data, almost 2 million Ukrainians, or 1.4% of the total population, lived in Russia, making them the third largest ethnic group after Russians and Tatars in Russia.

The ethnic policy of the USSR never promoted Ukrainian identity, although it declared national equality. And the highest peak of Ukrainian activism in Russia was the time of independence of "greater Ukraine" in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

It was during this period that national and cultural centers of Ukrainian life in Russia were created. Schools, including Sunday schools (for language and culture), clubs, branches of the Prosvita society, art magazines, the press, musical groups, and libraries began to function. Ukrainians in Russia established close contact with Ukraine.

How Ukrainians began to be harassed

The example of the Kuban Cossack Choir is indicative of many processes of the recent Russification of Ukrainians in Russia. In the 1990s and into the 2000s, this group often toured Ukraine. Among its members, a significant number were Ukrainians from the Kuban, and its repertoire included Ukrainian songs. The head of the choir, Viktor, assured me that they continue to preserve a strong Ukrainian tradition, and that they speak Ukrainian ("balachka") in everyday life and during rehearsals, although less and less

But. Since 2014, Viktor Zakharchenko has been included in the Myrotvorets list for supporting the annexation of Crimea and signing a letter in support of Putin. We know that during the recent presentation of a Russian award to him, Zakharchenko said that he was "praying for Putin" because he was fulfilling his "royal duty." As far as we can tell, the choir has completely switched to everything Russian.

So, when did this shift occur? What preceded the transition of the Ukrainian diaspora's rapid flourishing into a silent desert?

The bifurcation point is 2008, when the Russian side began to curtail Ukrainian organizations. And this process began simultaneously with the attack on almost all officially registered organizations. The first to come under pressure was the Union of Ukrainians of Russia (UUR), the central coordinating organization for the Ukrainian national minority in Russia, established in 1992 and registered with the Ministry of Justice in 1994.

Oleksandr Alfyorov

Oleksandr Alfyorov, a historian and currently an officer of the 3rd Separate Assault Brigade, believes that the reason for the searches, criminal proceedings, and the official closure of the UUR in 2012 was Russia's invasion of Georgia: "2008. At that time, Georgia's political support led to such a warning against Ukrainians. And this warning came from the Kremlin."

Askold Lozynsky cites another argument: the loud commemoration of the Holodomor anniversary by Ukrainians in Russia in 2008 demonstrated to the Russian authorities the attitude of Ukrainians: "Moscow began to persecute Ukrainians for commemorating the Holodomor, and then began to close all representative offices in 2010 when Yanukovych came to power, because they knew that Yanukovych would not protect Ukrainians."

Since 2012, cultural centers have been under pressure, including this iconic institution, and the last of a series of closures, the Ukrainian library in Moscow, which was finally liquidated by the authorities in 2017, after the annexation of Crimea and the occupation of part of the Ukrainian East.

The Ukrainian authorities reacted to these closures with a very sluggish response, limiting themselves to official statements. As a result, the Ukrainian community in Russia became "invisible" to both the global Ukrainian community and the mother country. As Askold Lozynski notes, "Putin began to eliminate Ukrainian central representations. In addition, in 2016, the World Congress of Ukrainians was added to the list of undesirable organizations in Russia. Organizations that still remained in Russia had to retreat from the World Congress. But the World Congress lost interest in them as well. Thus, Ukrainians in Russia lost their voice in international diaspora organizations."

Vitaliy Portnikov, a journalist and publicist, Shevchenko Prize winner, has been living in Russia for a long time and contributing to the creation of Ukrainian communities. Recently, he predicted a fatalistic outcome for both national diasporas of the neighboring peoples, Russian and Ukrainian, saying that if the war continues, they will finally disappear: "The history of coexistence between the two neighboring peoples, who had multimillion-dollar diasporas in the territories of Ukraine and Russia, is coming to an end before our eyes. And all we can do is to preserve the historical memory of the lands where Ukrainians once lived and their unique civilization on these lands, from the Green Wedge to the Kuban. But we are unlikely to ever meet 'living' Ukrainians on these lands."

Instead, Askold Lozynski is convinced that Ukrainians in Russia not only exist, but are still waiting for Ukrainian support: "They themselves want contact. They are desperate for contact. I have a concept that there was a lot of migration in Ukraine during the war. So Ukraine should open its doors, but very carefully, to Ukrainians who are from Russia. And to make it possible for them to renounce their Russian citizenship and take Ukrainian citizenship in some time."

The issue of security of existence for those in Russia who are still convinced Ukrainians is one of the reasons why, according to Aleksandr Alfyorov, the Ukrainian authorities have not been very insistent on returning rights to Ukrainian communities: "I know that Ukrainian activists in Russia have been persecuted, and any support from Ukraine only added to their imprisonment or more fines. We also remember the introduction of the rules on foreign agents in relation to NGOs and public figures. And it's clear that no one was willing to endanger them. To be honest, in 2014, I did not see any attempts to really expand the activities of Ukrainian organizations in Russia because of the very beginning of Russia's war with Ukraine. We understand that there are security issues, especially with regard to those who joined the Ukrainian underground. They are a minority, we do not hear their voice, but they are there."

What do we have now?

The level of visibility of Ukrainians in Russia, the importance of this diaspora, began to fade in 2008, and this happened because of Russian policy. The number of people who identified themselves as Ukrainians fell by one million from the 2002 census to 2010. With the outbreak of war in 2014, and the full-scale invasion, there was certainly no incentive for ethnic Ukrainians to identify themselves as Ukrainians, even if they had a national identity. As Lozynsky notes: "Really, what good would it do them if they said in the census that I was Ukrainian?"

Alferov, like Lozynsky and Portnikov, notes that there is not a single representative organization of Ukrainians in Russia today. "In Russia, there is not a single school where Ukrainian is taught, there is not a single publication, and there is not a single organization, library, or club where Ukrainians could gather at all. Everything was eliminated by the beginning of 2014," emphasizes Aleksandr Alfyorov.

Meanwhile, Askold Lozynski continues to communicate with the diaspora. Those of them who still remained in Russia with openly Ukrainian views are now leaving the country out of fear for their lives: "I talk to them every few days. For example, there is Valeriy Semenenko, the head of Ukrainians in Moscow, who arrived in Kyiv only 3-4 months ago. They were constantly coming to his house and searching it. The second is Mykhailo Volyk, who was active in St. Petersburg [now he has left for Yerevan because of pressure from Russian punitive authorities]. Serhiy Vynnyk, the head of a local organization, left for Canada from the Omsk region. There are many Ukrainians with whom I am in contact, and many of them have left. They have no future in Russia."

Most of them, since they have Russian citizenship and the border between the two countries is closed, were forced to go to Ukraine through third countries, such as Armenia and Kazakhstan. The question raised by Lozynsky about the cautious but return of Ukrainians who want to leave Russia should also be raised. But so far it is not on the agenda.

A decree that was 15 years overdue

Whatever the reasons, whether it was Yanukovych's pro-Russian views or security issues under Poroshenko, there has not been a single official document since 2009 that would regulate, support, or signal to Ukrainians in Russia that they have not been forgotten. That is why Zelensky's decree on the historically Ukrainian-inhabited territories of the Russian Federation was welcomed by all those who are involved in and interested in Russian-Ukrainian relations. Oleksandr Alfyorov, a scholar who has studied the history of these lands, explains certain accents: "This is a unique decree that I absolutely support. In fact, it challenges the Russian system, which on international platforms says that someone in Ukraine allegedly harassed someone for the Russian language or the Russian church, and instead came to Ukraine with weapons and brought genocide. We will also be able to demonstrate on world platforms that this war is not only unfair and unjustified, but it is a continuation of the conflict that the Russian state started in 1917.

Lawyer Askold Lozynsky also has positive expectations, in particular, regarding the moral support of Ukrainians in Russia: "I called Volik and told him about this decree. And he said: Amen, it has finally happened. Yes, Ukrainians there understand that the decree will not be of much importance for their protection, because Russia is not governed by laws. But it is important to them that finally their mother country is interested in them and cares about them. And I can tell you that this will be a calling for them. Not to create a revolution in Russia, but to leave, escape and go to Ukraine. And the law is very much needed. It's 15 years overdue, but it's good, at least now. Volodymyr Zelensky is the only president who is interested in the Ukrainian diaspora in Russia, and this is important."

So what about the Green Wedge?

One of the questions that remains on the mind is why the decree does not mention the territories of the so-called Green Wedge inhabited by Ukrainians. For example, Askold Lozynsky doubts that without the Green Wedge we can talk about the Ukrainian diaspora in Russia. Moreover, it was also affected by the processes of denationalization and even persecution of Ukrainians.

Alfyorov explains the absence of territories separated from Ukraine by thousands of kilometers in the document as being aimed at an international audience, which he says may raise certain questions for the Ukrainian side: "The Decree is aimed at the external diplomatic community. If we had mentioned other Ukrainian ethnic territories scattered across the Russian Federation, we would have defocused attention on Ukrainian ethnic lands located along the Ukrainian border in the Russian Federation." The historian notes that focusing on the border areas allowed them to speak clearly, without claiming "any islands in the Russian Federation, which would have allowed Russian propaganda to start saying that, well, you see, "Ukrainians dug up the Black Sea and settled Kamchatka." This is the right decision to deliver the right message to Western diplomats."

Even without identifying all Russian territories inhabited by Ukrainians, the Decree gave impetus to scholars and researchers to work on the concept of Ukrainianness as a concept not limited to the territory of Ukraine. To study the methods by which the Russian ideological machine destroys the Ukrainian ethnic minority in its country. And to look for mechanisms to help those who are waiting for Ukrainian support. Even if there are no longer a million of them, every Ukrainian person is important to us. Especially during the war.

Yaryna Skurativska, Kyiv