Mariupol. Escape from hell. My story

This is a follow-up story. Read the beginning here

... Three weeks have passed, and I no longer believe there was once a different life. In that different life, we slept in beds, ate to our heart's content and enjoyed the sun. Now we take turns huddling on chairs, counting corn kernels and watching how an oil lamp smolders in a saucer. Along with it, there is a weak hope. I feel sorry for myself, my loved ones and people I didn't know before. I look at Olenka - she is not sad, and it would be a shame for us, adults, to let it go.

On March 15, a humanitarian corridor opened in Mariupol. People were allowed to leave in their cars, but no one declared a ceasefire regime. Four of our neighbors were saved. It was possible to get to Melekine (a resort village between Mariupol and Bilosaraiska Spit) for $2,000 per person. We didn't risk running to the garage under bombardment and didn't know if our car could survive. In the evening, it was reported on the radio that several thousand cars had escaped from the city. Rumors spread immediately about those who failed to get to the destination and hit landmines. On the same day, my mother's godmother came to our basement, her house was hit by shells, the windows in the apartment were broken and half of the kitchen was destroyed. Wrapped in a sheepskin coat, she kept repeating: "How warm it is here, how warm it is here," with steam coming out of her mouth.

Time in the basement passes so slowly. You are constantly waiting for death, and it seems inevitable. "Every evening, I looked at the ceiling and asked God not to bury us under the rubble," my mother admitted to me later. I begged for my arms and legs to stay with me, in place.

Photo: Evgeniy Maloletka

The supplies of food and water were running out. Olenka and her brothers nibbled on raw potatoes and asked for a drink. Only once did I see their mother cry. Street fighting was going on in the city, and the front was passing above our heads. "One or two days and everything will be over," we repeated as a mantra. However, it only got worse. We knew that the Kadyrov fighters had entered the city. There were legends about their atrocities. The maternity hospital, the Drama Theater and the Neptun pool have already been bombed. Mariupol was shelled from the sky, land and water. Houses were crushed and razed to the ground. We decided to run away.

Photo: AA

"R.I.P. Mariupol"

There is a deathly silence in the street. This is a good sign. The entire yard is littered with shrapnel and covered in layers of ash, glass and plastic. We are holding a bag, once used for potatoes, with the remains of our former life and a turquoise suitcase. We are waiting for others. Our sleepy fellow travelers slowly and cautiously get out of the bomb shelter.

I remember us taking a sip of holy water before we left (my dad miraculously found it in the ruins of our apartment). "Walk at a steady pace, don't run, snipers are working," we explained to the children. Doubt was visible in the eyes of those who remained: "Where? Why? You won't make it." But we chose to go. We learned the way from those who have already used it: we went to the METRO shopping mall through the wholesale market and the cemetery. It was a long way to go, but they didn't shoot there.

All around is a sleeping city, burnt houses, crippled streets. There are no cars, no voices, no sound, just soft sobs. Tears burst out. "Don't turn around, just don't turn around," someone whispers from behind. "But I wanted to say goodbye," Mom apologizes.

Photo: AA

Nine-story buildings not affected by shelling were guarded by DNR soldiers. They stood guard at the entrances and suspiciously examined our documents. We left Olena and her family in the private sector. The children were happy to be back, and I looked at a leaning house with a hole in the roof and did not understand: "How will they live?" Farewell was short-lived. The tanks had already "awakened" and heavy shells exploded somewhere far away.

Our journey seemed endless, I walked and muttered a tongue twister all the time: "Save and protect, save and protect." Death seemed to follow us. Behind us a boy was dragging his father, who was slowly dying. Near the regional hospital, a man gave up, fell on the bench and stopped moving.

Someone wrote "R.I.P. Mariupol" with a finger on the dusty glass of a broken bus.

Photo: AA

Liberators

The gaze of thousands of eyes, filled with hatred and contempt, turned upwards. "Liberators" are going. A column of tanks crawls slowly, savoring every meter of the road. The orcs sit proudly on their armor and look at their "slaves." Now they will open the barrier and let the hungry crowd to the feeder.

They opened their headquarters at the METRO shopping mall. Here, they set up the "United Russia Assistance Center" and hang the tricolors. People stayed in line for seven hours - they were given stale bread, cereals, canned food and water. Medicines were given separately. Everything was packed in boxes with a Z label and the cynical inscription "We don't leave ours behind." A voice on the loudspeaker insisted that people go to Rostov and Donetsk. "We don't take anyone to Ukraine," a man in a military uniform told me.

The wind pierced my bones. I looked at people, but saw only shadows. They moved, spoke, fought for humanitarian aid kits and cried out of despair. I also saw myself as if from the side. I am greedily drinking from a bottle of water thrown by someone. I am clinging to a seat on the bus, pushing away a woman with a cat.

We decided to go to Donetsk – we chose the lesser of two evils. But even here they deceived us. The buses traveled 20 kilometers and stopped in the village of Nikolske (formerly Volodarske), as it later turned out, for forced filtration.

Photo: AA

Filtration

The bus dropped us near the building of the local administration and went to pick up a new batch of Mariupol's residents. Confused and with many bags, we wandered towards the school, where they set up a temporary refugee camp - people slept on desks and on the floor. New arrivals were also registered there - for filtration and evacuation. Every day, buses left the school for Rostov and Taganrog.

We did not like the prospect of spending the night on the floor. There was no hotel in the village. I began to seek shelter from the locals. I could not solve the imaginary Rubik's cube in my head: 20 kilometers from the broken Mariupol city, people lived a peaceful life, pottering in the gardens, riding bicycles, and going to the store. The only reminders of the war were crosses with tape on the windows and white ribbons on the gates. "My daughter lives in an apartment building on the outskirts, the windows in her apartment were broken, but the village is intact, the tanks passed by and headed towards Mariupol," said Anatoliy, a native of Nikolske. He is the only one who volunteered to help and take us to an acquaintance who had an empty apartment. "There are already 16 of us in the house. In the first days, I drove and took relatives out of the city, then the road was blocked," the man said.

There was no gas in the village. We were offered a cold apartment without electricity or hot water. We did not hire it. My mother's godmother recovered from the shock and remembered her husband's relatives who lived in Nikolske, and eventually took us in.

Ukrainian communication was not available, banks and post offices were closed. Pharmacies sold leftovers. In the first week, we all started to get sick - the damp basement had its effect. There are crazy queues everywhere: for medicines, bread, toothbrushes. DNR soldiers, like cockroaches, spread around the village, sticking Z letters on the stolen cars. The filtration was carried out at the police station. Opposite, in the building of the Prayer House, a traffic police station was opened. Anyone over the age of 18, regardless of gender, was subjected to strict filtration.

People waited a month or one-and-a-half months for their turn. Without a filtration paper in the "DNR" universe, you are a louse. To return to Mariupol or to go further, everyone had to go through a humiliating procedure.

Before filtration, I cleaned my phone, switched it to English, closed my Facebook account, deleted messengers, and left only Instagram with neutral photos and Viber with casual correspondence. Filtration was like a gallows - any careless word and you could be considered untrustworthy. And this is a direct road to the Olenivka colony, a real concentration camp: torture, toilet and water once a day, no walks.

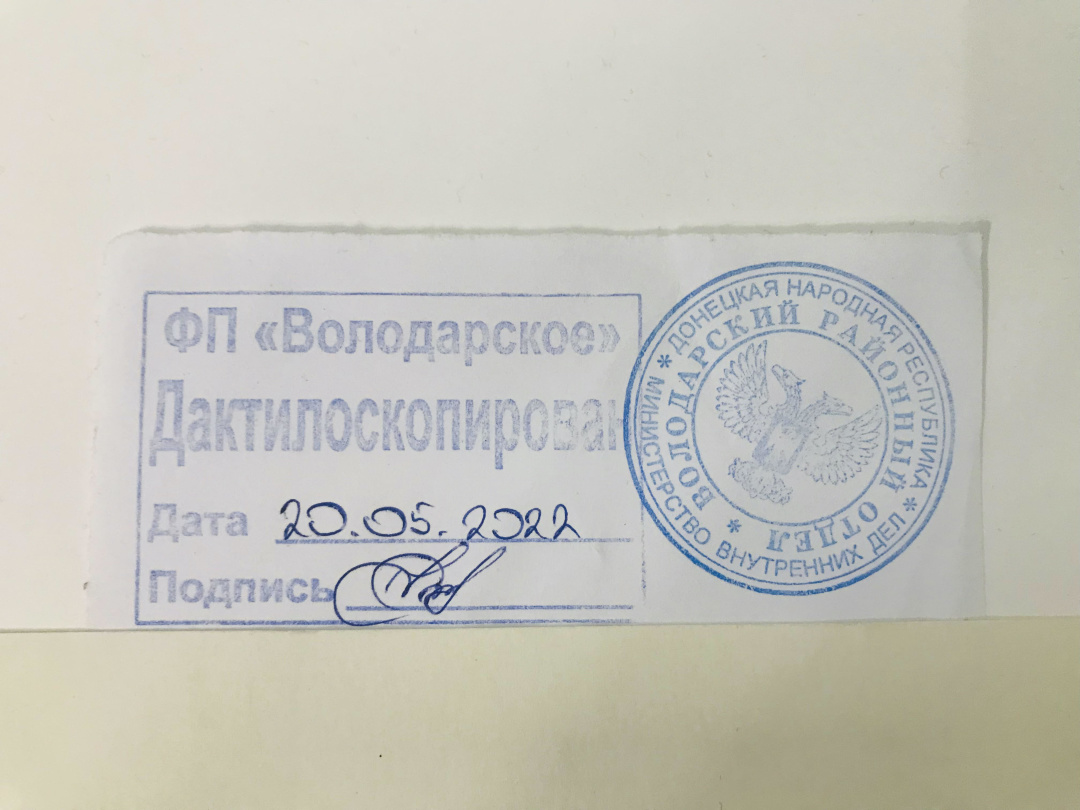

"Take off your outer clothes, leave your bags and personal belongings on the hanger," said a DNR woman in a military uniform. In a small room, there are five tables with scanners for fingerprints and palms, cameras on tripods nearby. I didn't take off my light jacket and I was immediately showered with abuse, unexpectedly interrupted a phone call. On the screen of the lady's phone, I saw that she received the call from her "darling" (also marked with a red heart) - the woman then began to behave more gently. Then she silently took my fingerprints and photographed me in front and profile. The atmosphere in the office was tense. I saw a man's fingers trembling from fear, his palms we sweaty - the device did not work at all. The woman was angry and grabbed his fingers.

After that, they were sent for questioning. In a separate room without witnesses, I was already being scanned with a glance. A big man asked me about my job, how I got to Mariupol, where I lived in 2014, whether my relatives serve in the Ukrainian Armed Forces, whether there are acquaintances in the Azov regiment and how I feel about Right Sector. I wrote something down on the form. Then I was ordered to give him my phone – he scrolled the screen for five minutes. In the end, he returned it and made me put a signature on a piece of paper.

I left the police building with a piece of white paper with the stamp "DNR Ministry of Interior" and the stamp "fingerprinted."

"Good evening"

While I was sitting in Nikolske and waiting for my turn to undergo filtration, my parents, as pensioners, passed it according to the accelerated procedure (the orcs were not interested in women over 60 and men over 65). They were allowed to leave the village.

At the family council, we decided to return to Mariupol and see if our car was not damaged. The taxi driver took UAH 1,000 for a one-way trip to the city.

Fortunately, our Mazda survived the bombing. First, we left for the occupied Berdiansk and then traveled through Melitopol to the infamous Vasylivka. There were no "green" corridors back then. We traveled risking our own lives, like thousands of people who wanted to escape from the occupation.

In the damaged parking lot in front of Vasylivka, they formed columns of ten cars. We arrived early in the morning, but already led the 13th column. "Get ready to spend the night here, only 70 cars were allowed in yesterday," a young woman with a five-year-old girl stunned us. I looked around in all directions: mothers with children, pregnant women, the elderly, and disabled people. All of them became hostages of the occupiers in a small area in front of Zaporizhia.

During the day, the Chechens with assault rifles walked like peacocks between the cars and looked in the windows. Residents of neighboring villages brought pyrizhky (stuffed buns), water, tea, coffee and strawberries to the parking lot. The transporters said that in April they spent five days in the parking lot, put up tents so as not to huddle in the car, made a fire, and cooked.

They started allowing the columns in only in the evening – at most 80 cars passed from five to eight. We spent the night at a gas station. We tried to sleep to the sounds of cannonades, the shelling did not stop until morning - there was nowhere to hide. Cars and a clean field are all around. After a day and a half of waiting, our column finally left for Zaporizhia. Ahead of us were four enemy roadblocks and the most dangerous "gray" zone.

"Father, where are you from?" a young man with a Russian accent stopped us at the first checkpoint in Vasylivka. My father said that we were heading from Mariupol. "From Mariupol?" he asked surprisingly. He did not check the car, but quickly examined our passports and let us go. In the end, he expressed his sympathy (some higher degree of cynicism). Relatively easily, we passed three more checks. They examined the trunk, the glove box, randomly opened and rummaged through our bags. At the last checkpoint, a soldier in a balaclava clicked something on my phone for a few more minutes.

In early March, the occupiers broke a bridge across a river in the Kamianske district (a village in the gray zone). From then on, it is only possible to drive to Zaporizhia on a dirt road. We were lucky, there was no rain for several days - and the road was not washed away. We drove carefully. Other cars with low ground clearance hit the ground. As soon as we passed half of the way, we heard explosions. The village was shelled with heavy weapons, but miraculously we climbed the hill and saw the first Ukrainian checkpoint. Our guys, quite young, were sitting near the broken house.

"Good evening," we heard our native language. They understood that we had escaped from hell and burst into tears.

Zara Maksymova