Went to evacuate his family from Mariupol and was taken hostage

One of the most common crimes committed by the Russian occupation army in Ukraine is arbitrary detentions and taking hostage of civilians. Under international law, such actions constitute a war crime, at the very least. Depending on the scale and systematic nature of the practice of deportation of Ukrainians to specialized detention locations, we can also be speaking about the commission of the crime against humanity, which is an even more severe international crime.

This was practiced particularly heavily in the southeast of Ukraine and in Kyiv, Chernihiv, Sumy and Kharkiv Oblasts, occupied in the first weeks of the full-scale invasion. Civilians were detained without reason, arbitrarily, often even without any explanations of reasons – at the block post on in the street, in the “filtration” center or in their own homes. After interrogations and beatings, some were released, but most were taken to the territory of the Russian Federation. Just like our colleague, UNIAN reporter Dmytro Khyliuk, whom occupiers captured in the street of his native Kozarovychi in Kyiv Oblast together with his father – a 75-year-old man was lucky, and he was released. His reporter son, however, is still in captivity at an unknown detention location somewhere in Russia.

It is currently unknown how many of those ordinary civilian people were captured by invaders, as Russia does not provide information on detained civilians to anyone. Media Initiative for Human Rights (MIHR), which is dealing with investigations of Russian war crimes, particularly forced disappearances, identified 948 civilian hostages detained in the RF and occupied territories as of April 2023. However, as emphasized by the Initiative, their actual number “could be 5–7 times larger.”

Based on reports from the relatives whose loved ones had been detained by the Russian military, the Parliamentary Commissioner for Human Rights Dmytro Lubinets estimated this figure as nearly 20 thousand people. Based on his forecasts, this number may become even bigger once the occupied territories are liberated.

Photo credit: mipl.org.ua

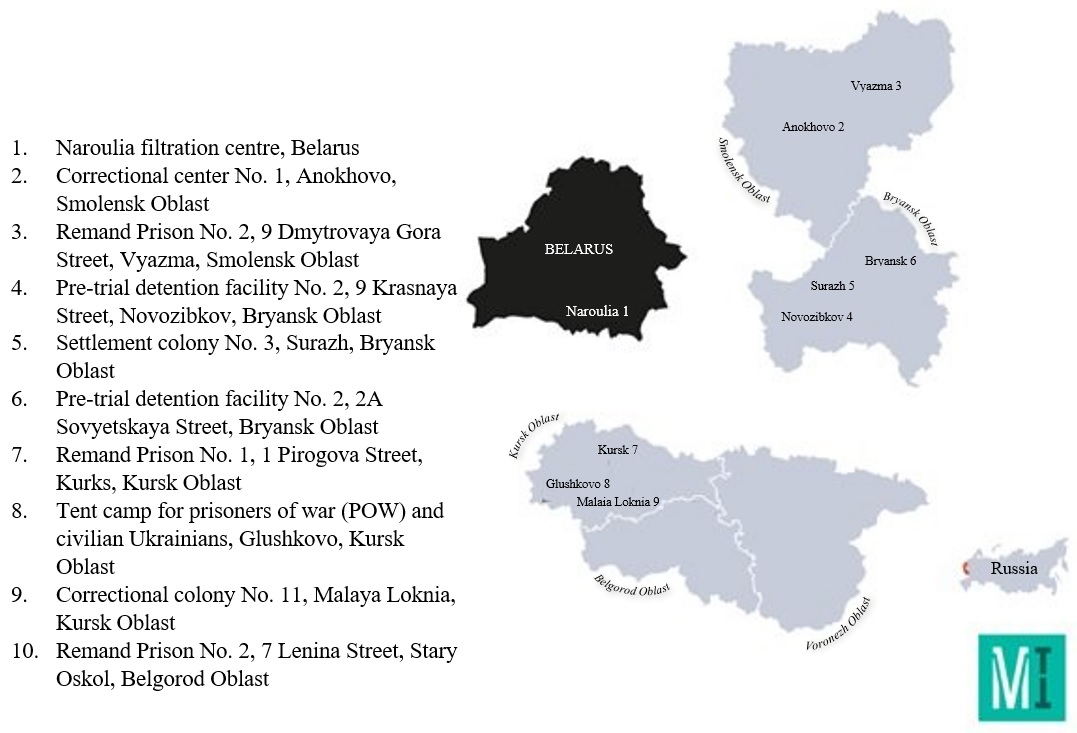

Civilian hostages are detained in occupied territories of Ukraine and in the Russian Federation, they are being continuously moved, including deep into the RF. In addition, MIHR recorded cases when people were detained in Belarus – in the filtration camp in Naroulia, nearby the Ukrainian border. Based on the testimonies of former captives, MIHR developed an interactive map of locations where the RF used to hold or is still holding civilian hostages and prisoners of war – over 100 locations, from Donetsk to Kherson and Irkutsk Oblasts.

Despite their status as non-combatants, invaders treat detained civilians as Ukrainian POWs, with whom they are often held together, i.e. by normally applying psychological and physical violence.

Photo credit: mipl.org.ua

Last Friday, this crucial topic of arbitrary detentions and taking hostage of Ukrainian civilians became the object of attention at the OSCE headquarters in Vienna, where missions of Ukraine, the EU and the USA, together with MIHR, held a private event “Missing in Occupation: Where Is Russia Holding Ukrainian Captives.” Delegations of participating countries could review the map of locations used by Russia to detain Ukrainian civilian hostages and listen to testimonies of survivors, including the former hostage Viacheslav Zavalnyi, who was captured by occupiers during an attempt to evacuate his family from Mariupol in March last year.

Right before the event in Hofburg, a former captive who had spent 10 months in Russian captivity shared his story at a meeting with reporters in the building of the Ukrainian mission at the OSCE.

DETENTION AT THE BLOCK POST, BEATING AND IMITATION OF SHOOTING

“On the day of the full-scale invasion of the Russian Federation, my family was in Mariupol while I was in Kyiv. All communication with Mariupol was lost on 4 March. Messages of horrible destruction and hostilities, which moved to the city center, started appearing in the media. On 5 March, my son turned 7. He had to celebrate his birthday in the basement of his house under shelling. I was forced to take a car and go there to evacuate them,” 53-year-old Viacheslav Zavalnyi, an engineer who worked in a bowling club, started his story.

At the time, the Russian army was stopped around Orikhiv, Zaporizhzhia Oblast, nearly 200 km from Mariupol. Hostilities were going on in this region, and civilians were not allowed to go to the territories taken by Russians for security reasons. Because of this, Viacheslav had to wait in Zaporizhzhia for about two weeks. He monitored Telegram channels and saw that his district in Mariupol was “completely destroyed.” On one of these days, his wife got in touch with him. She managed to charge her phone from the generator and come up to the place with mobile coverage. The next day, on 22 March, the man “managed to break through the demarcation line,” although he immediately came under fire.

When he covered about 50 km, Russians detained him at the block post. According to the engineer, he caused suspicion because of his age, as at the time, he looked much younger than his 52. Furthermore, the Russian military found a map of hostilities on his phone – one of the images posted on Telegram and tracked and shared by people to better understand where exactly the hostilities took place.

“The soldiers that were guarding me at first did not show aggression, they were just waiting. When officers came, everything changed – a tough interrogation started. They suspected me of being a Ukrainian intelligence officer,” said Zavalnyi. “They fired a gun near my head, then smashed my face with the gun and shot near my legs. They demanded that I signed a confession.”

Later, along with other detained civilians, he was sent to “dig his own grave and get ready for shooting.”

“It was staged, we were not shot. But they shot one person digging his grave in the leg. They regretted not being able to shoot us right away because of some order,” the man noted.

After this, arbitrarily detained civilians spent about three days in the basement waiting to be “transferred somewhere further.” During this time, they were given food and water only once.

However, the situation was especially difficult for two Ukrainian soldiers who tried to get out of the encirclement by changing into civilian clothing – “they were being beaten all night long.”

Photo credit: mipl.org.ua

INTERROGATION OF THE CIVILIAN “RESEMBLING A UKRAINIAN OFFICER” IN MELITOPOL

After this, Viacheslav and three other men were packed into the pickup truck with their hands tied and eyes covered and were taken to a new “interrogation site”. As it turned out later, this was Mariupol occupied by Russians.

“Upon arrival, we were beaten. They took away all the personal belongings we had with us. Then, they took us to interrogations and spoke with each one privately. I asked to call my wife to let her know that I would most likely not come. They allowed me to do it, as they wanted to know where I would actually call. After all, they suspected I was a spy, and this way, they wanted to find out at least some clue to confirm these suspicions.

All this time, detainees were lying on the floor, they were taken to the bathroom blindfolded.

The Russians were prepared for interrogations and checking captured Ukrainians. They checked every detainee against available MIA databases for service in the Armed Forces of Ukraine, issued weapons, etc.

“In my case, it disappointed them even more and caused new suspicions. By appearance, I looked to them like a Ukrainian officer, and there was nothing in these databases, as I did not serve in the army,” Zavalnyi said.

According to him, he urged the Russians to let him go to evacuate his family, which was under shelling in Mariupol.

“They told me, “Most likely, you will be exchanged.” All subsequent months, while being in jail in Russia, I was constantly thinking of this phrase,” Zavalnyi noted.

OLENIVKA AND “SITTING HERRINGBONE-STYLE” ON THE WAY TO THE “EXCHANGE”

Detained civilians – and there were almost 25 of them, along with Viacheslav – were transferred from Melitopol to the colony in Olenivka near Donetsk, which occupiers turned into the filtration camp.

“There, we were in a barrack with the military. There was no separation. You could distinguish us this way: if this was a civilian, he was wearing civilian clothes, and the military who were detained as a result of hostilities were wearing uniforms.”

The man spent two weeks in Olenivka. According to him, the filtration camp has expanded considerably: if there were 600 people at the time of his arrival, the number reached almost 2,000 when he was leaving.

“I spent two weeks there. Then, the cars arrived, and a Russian officer without any insignia and wearing a balaclava appeared. He said that we were going for exchange. And he took the first 100 people from the barrack where I stayed. We were in the second batch. It was on April 15.”

Leaping ahead, it is worth noting that no one was taken for exchange from Olenivka at that time. “When I returned, I found the families of the people who were with me in Olenivka and left in that first batch of 100 people. They turned out to be in Voronezh, Taganrog, across the RF,” the former captive will later note in his conversation with reporters.

At that time, in April, men were taken “for exchange” in a truck, seating them on the floor in a special way.

“I was told that for our own safety and for us to get to the destination safely, we had to sit in the car in a special way. Then, I learned that at NKVD, they called it “sitting herringbone-style”. Everyone sits in the back of the truck, and hands are pushed under the armpits of every next person and then handcuffed. “The handcuffs would tighten at every pothole,” – told Viacheslav. – We were on the road all night long and found ourselves at the airfield in the morning. They spent about 30 minutes taking off the handcuffs from my hands because they were tightened so much. People had to ease themselves in the car while sitting on the floor. During this trip, savage yelling did not stop. It was especially hard for those who were sitting in the front of the truck, as all the people were sliding onto them.”

At the airfield, captives were blindfolded with tape and seated in a transport aircraft. After several hours of flying, they disembarked and packed into the prisoner transport vehicle and delivered to the Russian jail – Kursk remand prison No. 1.

TORTURE IN KURSK REMAND PRISON AND MAD INVESTIGATOR

“According to the traditions of this institution, we were immediately beaten at the so-called “admission.” This time, I was very lucky as I staggered when they were leading me out of the cell – either because of fatigue or because someone pushed me, and I hit my head on the corner of the door. There was lots of blood, and they had to bandage me. Due to this, I was not beaten. All others were being beaten until morning. We could see that people who were beating us had consumed alcohol, as they had alcohol-laden breath.”

According to Viacheslav, the remand prison administration treated civilian hostages from Ukraine differently from criminal prisoners detained there, who could move there and were visited by lawyers.

“They treated us differently. We had inspections in the morning and in the evening when we were taken to the hall and beaten. There was a man in my cell, a civilian from Volnovakha, affected by war just like Mariupol – it just does not exist now. All his relatives died as a result of hostilities. When he was detained, he did not even manage to bury his nephew, his body stayed somewhere at home. It was a good-natured, ordinary civilian person. Every time when they took him to the hall and started beating him, he just could not hold back... it was running down his legs. They also used a dog and baited it, and the dog bit some of the prisoners.

While in the colony, prisoners submitted samples of nails and hair for a DNA test, as they were told. While waiting for their turn for the “procedure” and numerous interrogations, they were standing in an unbearable position – on their knees, with hands handcuffed behind their backs.

“On one of the days we were taken to the investigation committee handcuffed, military police came. I was impressed that there was Stalin’s bust and portrait in the investigator’s office. At the end of the interrogation, I started feeling like I was talking to a madman – he said that they would destroy our cities and erase them until we surrendered,” Zavalnyi said.

According to him, an investigator named Valeriy Donetskiy “wrote my story in the epistolary genre” and gave it to me to sign. Viacheslav signed it in the presence of a witness.

“Perhaps, they still did not know what was going to happen to us, as these were just the first month and a half of the war, and everything was going contrary to Russia’s plans. And they tried to instill hope in us that we would be exchanged and released, that no one needed us. But, of course, after the move, tortures and this “admission” in Kursk, I did not believe anything.”

COLONY IN TULA OBLAST AND 33 GRAINS OF BUCKWHEAT PORRIDGE

He wasn’t wrong not to believe.

On 6 May, after new beatings, Ukrainian civilian captives were taken to the airfield and moved to another detention site – a correctional colony in Tula Oblast.

“We came, and everything was repeated: we were beaten again and thrown into cells. There were 24 people in our cell. All of them were civilian, but for one man. This place is located in the city of Donskoy in Tula Oblast, a correctional colony “IK-1”. We were accommodated in a separate building within the territory of a big colony.

At this point of his story, the former captive focused the attention of reporters on the following: “Note the names of these prisons because they have their governors, which are well-known. I believe these people must bear the same punishment as heads of concentration camps after World War II.”

Illegally detained Ukrainian civilians had no connection with the outside world. They did not even know the date or time of day.

“The entire summer of 2022 we were starved, they gave us very little food. Once, were counted 33 grains of buckwheat porridge. And we had 50 grams of tea or even less. People were exhausted,” a former captive told his story about horrible conditions in the Russian colony. “We were taken outside and beaten for no reason. We had to stand all day long, they did not let us sit down. Depending on the tyranny of a person on shift, we had a different number of squats to do, sometimes, the number could reach 3,000.”

The situation with health care was no better. There was a man in Viacheslav’s cell with gas gangrene on his legs, he was given strong antibiotics.

“Those who had healthcare issues had to go up to the second floor when they were being led to the healthcare post. On the way to the healthcare post, they were beaten. The same happened on the way back. This was called health prophylaxis.”

RETURN AFTER EXCHANGE AND ISSUES OF RELEASING CIVILIAN HOSTAGES

Viacheslav Zavalnyi is convinced that he managed to survive because he was physically fit and engaged in sports. He got a chance to be released and return home only on 8 January 2023 – as a result of the exchange.

“My family had to leave the occupied territory on their own. It took them three weeks. They had no food, no money,” he adds after finishing his story when answering reporters’ questions about the fate of his wife and son. “They are now in Berlin. We haven’t met yet. We are only talking via Skype. I cannot leave, we have war.”

“Were you released?” reporters ask once again about the circumstances of the release.

“They (Russian side – ed.)? They don’t release anyone. I was exchanged for a Russian military. You have to understand that they will not just release anyone,” a former civilian hostage answer.

And notes that he was a hostage: “I was in the territory of the RF. This is a grave war crime – to abduct Ukrainian nationals and move them to another territory. There is a term for this – hostage.”

According to MIHR, in Russia, Ukrainian civilians are formally often accused of committing “acts of international terrorism,” “high treason,” and opposing the “special military operation.” However, most of them are detained even without any charges pressed, and Russia gives information about them neither to their relatives nor to Ukraine or international organizations.

And this is a big issue. After all, the lack of any status for civilians arbitrarily captured by the Russian military complicates the process of their return home. There are virtually no legal mechanisms to release them, as these people should not have been detained in the first place.

According to MIHR, some civilian hostages were made to dress in the military uniforms by Russia and exchanged as if they were prisoners of war for Russian POWs. Other civilians are simply exchanged together with the military. Some are released in the same way as they were detained – without explaining the reasons. Many civilians staying in occupied territories, order their relatives to leave their native settlements after their release.

“When it comes to mechanisms, it is complicated, as according to international humanitarian law, it is forbidden to capture civilians. Only the military may be captured. Therefore, the international law does not provide clear mechanisms concerning the release of these persons. Because they had to be released under any conditions, as they cannot be captured,” Liubov Smachylo, MIHR analyst, answered during the press conference in Vienna about the possible mechanisms to release civilians detained by Russian occupiers.

And what about the role of the Red Cross?

“We know specific detention facilities in Russia. We asked the Red Cross to go there and visit those places. But they say it is hard for them to get access to these places, Russia does not allow it,” an MIHR representative noted. “However, we are convinced that the Red Cross has to increase the pressure on Russia to visit these places. As Viacheslav already mentioned, in these places, civilians and the military are held together. Therefore, according to the established practice, the Red Cross may visit such places. Another thing is that even when Russians give the Red Cross access, they hide civilians in such places before the visit or move them to other detention facilities because they know it is forbidden for civilians.”

“Did the ICRC or other international organizations contact you during the illegal detention?” I am also asking Viacheslav Zavalnyi.

“In the first 10 months, there – no”. The man’s short answer clearly characterizes the “efficiency” of efforts taken by the ICRC, the UN and other international organizations in the matter of the phenomenon of Ukrainian civilian hostages.

Vasyl Korotkyi, Vienna