The special tribunal for the crime of aggression against Ukraine must bring to justice those most responsible, including Russia’s political and military leadership, for this particular crime.

There is a discussion within the international community about the type and structure of the special tribunal and where it should be created. In Ukraine, this work is coordinated by the Office of the President of Ukraine. Andriy Yermak, the head of the Office, insists that the world needs the widest possible international institution of Russia's accountability for its aggression against Ukraine with the highest level of recognition.

One option discussed is to create a special tribunal based on a multilateral agreement among selected countries. This implies that Ukraine and the governments of other countries would sign and ratify an agreement on creating such a tribunal. Another option is to create a special tribunal based on an agreement between Ukraine and international organisations, such as the UN, which would adopt a resolution for a standalone tribunal. It would also be possible for Ukraine to create an agreement with a regional European organisation, such as the EU or the Council of Europe. In this option, the tribunal would be formally regional but, at the same time, international.

In any case, to create a special tribunal, Ukraine must gain support from as many countries as possible, as this will increase the chances of seeing Mr. Putin and the Russian leadership held accountable.

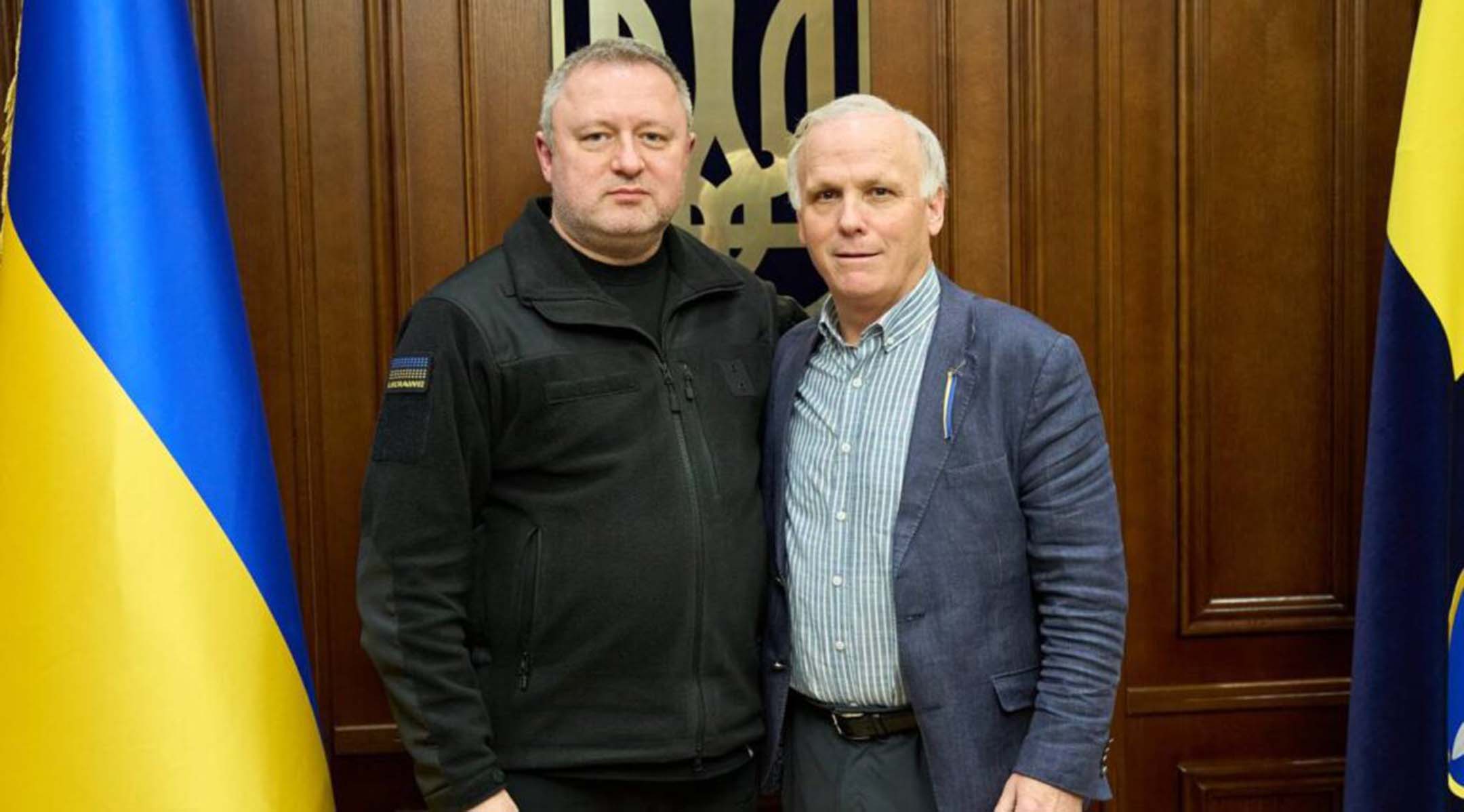

High-profile international lawyers, including Mark Ellis, an international criminal law expert and the executive director of the International Bar Association (IBA), are helping Ukrainian experts to achieve this goal.

In an interview with Ukrinform's correspondent in The Hague, he shared with us his opinion on how the special tribunal should be structured, whether we should wait until the war is over to create it, and how Putin can be brought to justice.

PUTIN IS THE MOST RESPONSIBLE FOR THE WAR IN UKRAINE

- How many times have you visited Ukraine? Can you, please, tell us how your meetings with Ukrainian lawyers went? Can you tell us more about the effort coordination to create a special tribunal for the crime of aggression against Ukraine?

- My visit in August was my third time in Ukraine since the war started. The IBA has been fast in its support of Ukraine and its condemnation of Russia’s war against Ukraine. During these visits, the IBA has signed several agreements with governmental entities, like the Office of the Prosecutor, the Ministry of Justice, the National School of Judges, the Ministry of Defence, and the Ombudsman, all aimed at providing IBA assistance as the largest organization of lawyers in the world.

Much of the attention has been paid to accountability issues to ensure those who committed atrocity crimes are brought to justice. This is a priority for Ukraine, and it’s a priority for the international community. Of course, when we speak about the crime of aggression, it’s a leadership crime, and that means that we are looking at Vladimir Putin as the most responsible for the war and this crime of aggression. However, the crime of aggression is still relatively new. It has only once been the focus of an international tribunal - the Nuremberg trials. During these trials, the crime against peace, essentially the same as the crime of aggression, was prosecuted.

But since Nuremberg, the crime has not been prosecuted. We know that the crime is now embedded in the statute of the International Criminal Court. However, there are limitations as to the Court prosecuting this crime because it requires the countries involved with the conflict to have accepted jurisdiction over the crime of aggression and be recognised as a State Party to the Rome Statute. Neither Russia nor Ukraine checks this box. So now we are looking at creating a standalone special tribunal for the crime of aggression since the ICC does not have jurisdiction over the crime regarding Russia.

- How do you structure this tribunal in a way that would effectively prosecute Mr Putin?

- There is a debate about the structure of this tribunal so that it would be effective and consistent with the requirements of international law for the tribunal to allow the pursuit of a sitting head state - Mr Putin. Therefore, that’s where the legal challenges exist.

- In your opinion, how should the special tribunal be structured? Kind of the Nuremberg tribunal?

- I hear people often talk about Nuremberg, and I think that the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg is an interesting example of the only time we’ve seen the crime of aggression (known then as the crime against peace) being prosecuted. So, from a substantive point of view, it’s good to look at the Nuremberg experience. But I don’t think the Nuremberg experience is relevant to what Ukraine is trying to do now. The reason is that it was a military tribunal, a tribunal that was created by occupying forces. And those forces had, in essence, control over the legal structure of Germany and its laws. I think it’s quite different from what we currently see for Ukraine. So, I think we have to be careful about that comparison.

AN INTERNATIONAL TRIBUNAL THAT WILL CONCERN ITSELF WITH THE IMMUNITY OF THE HEAD OF STATE

- What are the main possibilities for creating the special tribunal?

- The real question is how do you create an international tribunal for the crime of aggression? Should it be a UN-established tribunal? Should it be a domestic tribunal in Ukraine? Should it be an internationalised tribunal? I think those are the three interesting options – a purely international tribunal, or an internationalised one, or a domestic tribunal within Ukraine itself. I’ve always said that the crime of aggression is not a crime that Ukraine should solely prosecute because, for me, the crime of aggression violates the most sacred principle of international law - the violation of the territorial sovereignty of another country. Therefore, I have not supported having a domestic tribunal in Ukraine. Plus, a domestic tribunal, specifically created in Ukraine, would not get us over a major legal hurdle – head of state immunity, which Mr Putin is protected by. And so, the domestic model should be dismissed.

- What do you think is the best option?

- An international tribunal, created specifically for Ukraine would be the best option. But this is a challenging option.

- Why?

- Because to create a tribunal that could be seen as truly international, doing so through the UN Security Council would be the best option because, under the UN Charter, the UN Security Council has the ability to create these international tribunals, which it has done in other instances. But of course, the UN Security Council would not be able to do that because of Russia’s veto powers within the Security Council. Could the UN General Assembly create a standalone tribunal against Russia for the crime of aggression? There is nothing to suggest that the UN General Assembly has the legal basis to create an international tribunal for the crime of aggression against Russia. The Security Council can do that, but not the UN General Assembly. The UN General Assembly can recommend the creation of the tribunal, which is very important. This would be the best situation; at the request of Ukraine, the UN General Assembly adopts a resolution to support the creation of a standalone tribunal for the crime of aggression. This would give the tribunal a true international merit. However, there is no guarantee that the UN General Assembly will do that. We’ve seen previous resolutions condemning Russia’s war against Ukraine. And that’s good. However, I think securing support from two-thirds of the members of the UN General Assembly to adopt a resolution to create a standalone tribunal against Russia would be very challenging. I would certainly support this approach, but it will be difficult to secure.

There is the third approach which is an internationalised tribunal. In this scenario, Ukraine delegates its authority to prosecute for the crime of aggression to another group of states. It could be the Council of Europe, the European Union, or even a group of like-minded states that want to come together to create this tribunal. And then, this group would work to gain support from the international community to support the existence of this tribunal. I think this modality would work. So, I think there will be some type of internationalised tribunal at the request of Ukraine, to be created somewhere, probably in Europe, perhaps in The Hague. This modality would gain support from major countries like the United States, the UK, Germany, and France. I believe they would support an internationalised tribunal. I don’t think those countries would support a new purely international tribunal because they would be concerned about setting a precedent that would come back to haunt them. An internationalised tribunal, where they are assisting this new tribunal, would, I believe, be acceptable to them.

- Will this newly created tribunal be able to prosecute Putin, given the fact that he has the head of state immunity?

- We know that under international law, a sitting head of state being prosecuted by an international tribunal, like the International Criminal Court, does not enjoy head-of-state immunity. International tribunals do not recognise this immunity, which is why Milošević, Qaddafi, Al Bashir were heads of state and still prosecuted by an international tribunal. So, for me, the question is, in establishing this new tribunal, can you create it so in the eyes of the international community, it is a truly international tribunal that consequently does not recognise head of state immunity? Thus, it would allow this tribunal to pursue a sitting head of state. That is the crucial question.

WE DON’T HAVE TO WAIT TILL THE WAR IN UKRAINE IS OVER – WE NEED TO CREATE THE SPECIAL TRIBUNAL RIGHT NOW

- Some experts are sceptical about the idea of creating the special tribunal right now because the Nuremberg Tribunal, as well as the tribunals for Yugoslavia and Rwanda, were created after the war What do you think about it?

- You mention Nuremberg again, which is a good and interesting point. As I said earlier, The International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg was created after WWII, making it easy for the United States, the Soviet Union, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom, as they had supreme authority over Germany. This is not the case right now for Ukraine. But I don’t think we must wait until the war ends. I very much support the idea of creating the tribunal now, regardless of the modality. Nothing would suggest that we have to wait until the war is over. We have already seen the ICC indictment against Mr Putin. I think the arrest warrant will create more support and certainly raise awareness in the international community that we will hopefully pursue the crime of aggression against Mr Putin. As long as we can get over the head-of-state immunity hurdle and create an international tribunal to pursue a sitting head of state, then we will be successful.

- How can the leadership of Russia be brought to justice?

- I think it’s a good question. I believe that international criminal law and indictments and arrest warrants have an influence on justice. The arrest warrant against Mr Putin was historic. It was historic in the sense that we have seen indictments against other sitting heads of state. And I think it’s so important that the international community, through these tribunals, makes a statement and says that these individuals are committing crimes that shock humanity. That’s why we have the responsibility to bring them to justice.

That very statement, that arrest warrant, is powerful for me. But, of course, the next point is actually the ability to bring Mr Putin to The Hague. That’s a much more challenging and long-term process. Mr Putin is not going to be there tomorrow or any time soon. That’s the reality, and we should accept that. However, that should not deter us or disappoint us. I always say international justice plays the long game.

And history shows that these sitting heads of state are eventually brought to justice. Although they feel immune from the long arm of international justice, they are not. Because time and time again we see these individuals eventually brought to justice. There is no time limitation on the arrest warrant against Mr Putin. It lasts as long as he is alive and wherever he is. It’s difficult to think that Mr Putin would lose his support domestically, but eventually, that’s exactly what so often happens. Politics change, the environment changes and that’s when things shift. So, I say we just have to be patient. I believe Mr Putin will eventually find himself in The Hague. Again, it won’t be any time soon, but we must be patient. The arrest warrant is there, and I believe in it.

- In March, the ICC issued the arrest warrants for Putin and Lvova-Belova. They are suspected of having committed the war crime - illegal deportation, and displacement of children from the occupied Ukrainian territories to the Russian Federation, which has been taking place since 24 February 2022 at least. In your opinion, who else can receive the arrest warrant?

- The ICC set out the initial arrest warrant, but it is limited because it is issued on the specification of children being deported from Ukraine. I do not doubt that this indictment will be expanded. I think other accounts against Mr Putin and other Russian leaders will be added. The ICC has jurisdiction not only over Mr Putin but also any individual, political and military, who has engaged in these crimes. So, I also believe other indictments will be issued by the ICC, including against high-level officials. I have no doubt it will happen.

The other part of this equation is that the vast majority of war crime cases will not be conducted in The Hague by the ICC; they will be conducted domestically in Ukraine. Ukraine has the primary jurisdiction over these crimes and those who committed them. We know that Ukraine is already actively engaged in creating a mechanism, a domestic mechanism, to bring to justice those who have committed these crimes. Those individuals are primarily at the lower military level. They are not at the highest level. I think the highest decision-makers will be brought to justice through the ICC. However, the vast number of war crimes and other atrocity crimes that have been committed in Ukraine will be conducted by Ukraine, under its national jurisdiction.

I think you will see countries using the principle of universal jurisdiction to also indict and prosecute those individuals from Russia who have committed crimes in Ukraine. So, this concept of universal jurisdiction, in my opinion, will play an important role in ensuring accountability for these atrocity crimes.

- I dream and believe I will see Putin in The Hague one day. Thus, imagine that this day has arrived, and the special tribunal for the crime of aggression has been created. Moreover, there is the case at the ICC, I wonder how this will work. Will Putin be brought to one trial and then to another in The Hague? Is any specific cooperation needed because, without the crime of aggression, there would be no other crimes?

- The ICC has jurisdiction other than the crime of aggression. The special tribunal will be specific to the crime of aggression. I do not doubt there will be cooperation and understanding between the ICC and this new tribunal, if it comes into play, regarding the logistics and procedural issues of bringing and trying Mr Putin for these separate crimes. Thus, I don’t think it would be an issue. There will be communication and collaboration, and it will work itself out. The most important thing is that two separate criminal procedure routes will be followed - one through the ICC and another through the special tribunal that will have jurisdiction over the crime of aggression.

- In the past, the post-war tribunals did not prosecute the war crimes of the USSR. Why do you think no one was brought to justice?

- For me, why it did not happen after WWII is straightforward. The reason is that the world entered the Cold War. The Cold War froze bilateral and multilateral cooperation, including international justice. It was only after the end of the Cold War, more precisely after the fall of the Berlin Wall, years later, that international justice came back as the rule.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, we entered into a golden age of international justice. There was cooperation to create the international and domestic tribunals for Yugoslavia, Rwanda, Cambodia, Sierra Leone, and Lebanon. It happened because there was an environment that accepted the idea that atrocity crimes must be prosecuted and that those who have committed those crimes must be brought to justice.

So that’s why a gap existed between the end of World War II and the fall of the Berlin Wall. Only at the end of this timing did the possibility of creating new mechanisms emerge. And that, of course, was when the International Criminal Court was created, which is the permanent international criminal court to try individuals who commit these atrocity crimes. The ICC is meant to be the permanent court to pursue these types of crimes in the future.

And finally, one thing Ukraine has brought to the world is the vocabulary of accountability in fighting against immunity. Citizens who have never spoken of these issues before are doing so now. Students who never studied these issues are doing so now. Governments that were not necessarily interested in these issues are now focused on them. The focus on the issue of accountability and ensuring that individuals who commit them are brought to justice has never been as much in the public domain as it is today. And that’s because of what’s happening in Ukraine.

Iryna Drabok, The Hague

Photo credit: Mark Ellis, Ukraine's Prosecutor General's Office, Kateryna Lashchykova / Censor.NET