Russia officially withdrew from the Black Sea Grain Initiative almost a month ago, trying to prevent the export of Ukrainian agricultural products through domestic seaports by shelling its port infrastructure. Despite the hostile actions, Ukraine is making every effort to continue the sea grain corridor operations because global food security depends on it. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) commented on its risks to Ukrinform. In an interview, FAO Chief Economist Maximo Torero explained how food prices are rising worldwide due to the suspension of the grain deal stressing the importance of its resumption.

PRICE DYNAMICS AND FACTORS OF INFLUENCE

- What are the food prices’ dynamics and forecasts in the world?

- International food prices have been highly volatile in the last two to three years, first rising steeply starting from mid-2020 due to tight supplies across some critical staple food sectors, attributable primarily to a) COVID-19-related supply chain bottlenecks, b) increased global energy prices and c) weather-induced supply challenges. The war in Ukraine exacerbated the steep increase in food prices in February 2022, with FFPI jumping by 13.1 percent month-on-month. Vegetable oil and cereal prices rose by as much as 24.8 percent and 17.1 percent, respectively, in March 2022.

Since then, however, prices have been declining, reflecting increased global export availabilities, further helped by the Black Sea Grain Initiative (BSGI), which allowed maize, wheat, and other food commodity exports to continue. Challenging economic conditions across many countries and elevated international food prices also led to lower import demand, weighing on international food prices. Nevertheless, they remain elevated at historical levels.

Global food prices in the immediate future will depend on several global developments. First, how global markets react to the current market uncertainty, as the termination of the BSGI has added to already volatile world markets which generally have rather limited capacity to absorb additional shocks for net-food importing countries.

Second, while the world has ample supplies, especially of cereals, export restrictions such as the one imposed by India on white rice exports may add to market uncertainty and food price volatility. (In the autumn of 2022, India imposed a duty on the export of white and brown rice and a ban on the export of milled rice. And on 20 July this year, a ban was imposed on the export of all rice varieties except basmati.)

Third, the impending El Nino global weather phenomena (periodic warming of sea surface temperatures in the central and eastern regions of the Pacific Ocean) may have far-reaching implications on global food production in the coming months, possibly exerting further pressure on food markets and raising food prices globally.

On the other hand, challenging economic conditions in some large food-importing countries will counterbalance pressure for price increases to some extent.

THE WAR AND GLOBAL FOOD SECURITY

- How does the war in Ukraine affect these trends?

- In 2021, either the Russian Federation or Ukraine, or both, ranked among the top three global exporters of wheat, barley, maize, rapeseed, rapeseed oil, sunflower seed and sunflower oil. The Russian Federation also ranked as the world’s top exporter of nitrogen fertilizers, the second leading supplier of potassic fertilizers, and the third largest exporter of phosphorous fertilizers.

A large number of food- and fertilizer-importing countries, many of which belong to the groups of Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and Low-Income Food-Deficit Countries (LIFDCs), have relied on Ukrainian and Russian food supplies to meet their needs. At the time of the outbreak of the war, many of these countries were already grappling with the negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and rising international food commodity and fertilizer prices.

As a result of the war In 2022/23, the two countries together accounted for 9.0 percent of the global output of barley, wheat and maize (compared to 8.8 percent on average over the period 2017/18-2021/22), with the Russian Federation accounting for 6.5 percent and Ukraine for 2.5 percent (compared to 5.4 percent and 3.4 percent, respectively). For the oil-seed sector, owing mostly to a decline in the global sunflower seed production resulting from an output contraction in Ukraine in 2022, the share of the Russian Federation increased to 31 percent, while the share of Ukraine declined to 21 percent. Adjustments observed for other oil-seeds were small.

The share of Ukraine and the Russian Federation in the global exports of wheat declined to around 17 percent in 2022, from about 26 percent in 2021. Similarly, reductions of the share of the two countries in the global exports of barley, maize, rapeseed and sunflower seed oil were observed. Nevertheless, not all the changes in the trade and market profiles are caused by the war, although it has played a role.

- What is the role of the 'grain deal' and the consequences of its termination?

- Under the BSGI, over 32 million tonnes of agricultural commodities were shipped from Ukraine. The total amount included about 725 000 tonnes of grain shipped on vessels chartered by the World Food Programme (WFP) to support its humanitarian operations elsewhere.

Nearly half of the shipped volume was maize, while wheat accounted for slightly over a quarter. However, with the termination of the Initiative by the Russian Federation, pressure on prices is expected to increase.

Considering alternative – non-marine – shipping capacity, including shallow river ports, rail and, to a lesser extent, trucks, which Ukraine has developed since the start of the war, some exports from Ukraine will continue. However, despite delays during the inspection process in Istanbul under the BSGI, marine transportation via the Black Sea remains the cheapest shipping alternative.

Other shipping channels are costlier, and recently export and storage infrastructure in shallow ports was attacked. As such, a significant longer term concern remains whether, given the marketing (and other) challenges they face, Ukrainian farmers will continue planting, and what they will plant.

Already in 2023, some areas previously planted with cereals, was planted with oilseeds. Similarly, some farmland remains contaminated and mined, preventing farming. Should the war continue, further adjustments in the cropping areas in Ukraine are likely to reflect overall profitability of farming.

- Could you please comment on the consequences of the Kakhovka dam explosion? Will this disaster have an impact on global food markets?

- The June 2023 destruction of the Kakhovka dam, although with relatively contained short-term damages, has long-term environmental and economic impacts. Contamination will affect soil fertility, availability of drinking water for people and livestock, biodiversity and many ecosystems in the lower part of the Dnipro river.

In the long term, the use of irrigation systems, unless the water in the reservoir increases to the level that makes pumping feasible, will remain constrained. It is not foreseen that the loss of previously irrigated crops in the south would have a significant impact on world markets; however, the actual impact will largely depend on developments in other main producing countries.

WHO WILL SUFFER THE MOST

- Which countries will be most affected by this trend?

- While in general food exporting countries benefit from elevated prices, food importing countries pay higher prices for their food imports.

The global food import bill (FIB) is forecast to reach USD 1.98 trillion in 2023, representing a 1.5 percent or USD 28.9 billion increase over the record high registered in 2022, estimated at USD 1.95 trillion. While marking a new absolute high, the speed of expansion is anticipated to slow down significantly relative to 2022 and 2021, when growth rates reached 11 percent and 18 percent, respectively.

High-income countries (HICs) are anticipated to continue their usual imports covering most of the increase in the import bill, whereas upper-middle income countries (UMICs), lower-middle income countries (LMICs) and low-income countries (LICs) will focus their imports on staple foods and control import bills by lowering quantity and quality of their food imports.

Net food-importing developing countries are most vulnerable to rising international food prices. Among them, Sub-Saharan countries already facing severe forms of food insecurity, hunger, and even famine conditions are most at risk to deteriorate further. In addition to challenging economic conditions, most of these countries are also affected by ongoing conflicts. As the latest joint FAO/WFP Hunger Hotspots report highlighted in June, the countries with catastrophic conditions include Ethiopia, Nigeria, Somalia and South Sudan. This group also includes Afghanistan and Yemen.

However, even in countries currently not identified as Hunger Hotspots elevated global food prices are likely to keep food import bills high, often using precious foreign exchange, thus worsening balance of payment problems and contributing to inflation.

- What factors affect the rise in prices besides the war and Russia's termination from the grain agreement?

- Climate change and changing weather patterns will have implications on agricultural production as well as the processing and transportation of food. Some geographic areas will become more hostile to agricultural production, while weather conditions in others might make them more suitable.

Overall, the keyword remains 'uncertainty': uncertainty of changing temperatures, rainfall, and weather patterns. These concerns raise market uncertainty, contributing to elevated food prices.

Price changes will also depend on production and policy decisions elsewhere, especially related to vegetable oils and cereals. As we have seen this month, the export ban imposed by India on Japonica rice has led to higher demand from other suppliers, including Thailand, raising international rice prices. Reflecting this, the All Rice Price Index increased by 2.8 percent from June, with the index value rising to its highest level since September 2011.

The Vegetable Oil Price Index rose by over 15 percent. Indeed much of the increase was due to the end of the BSGI. Subdued production prospects of palm oil in major producing countries have exerted significant pressure on vegetable oil prices as well.

Meanwhile, soy and rapeseed oil prices increased on continuing concerns over production prospects in the United States and Canada. Rising world crude oil quotations also supported vegetable oil prices through the energy-food nexus.

WAYS OUT OF THE FOOD CRISIS

- What are the ways to improve the situation in the short term?

- First, the renewal of BSGI will contribute to dampening international prices and improve access and affordability of agricultural products for low and lower-middle-income countries. Many of these countries are already in dire macroeconomic situation, facing high level of debt, and higher import costs or economic volatility will significantly deteriorate their capacity to support their population.

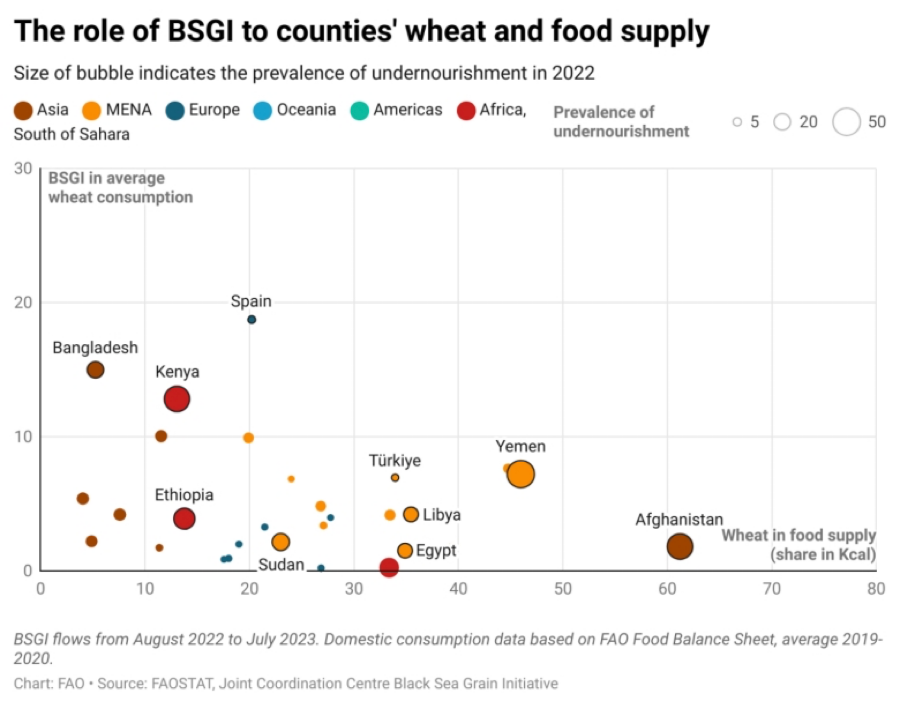

As shown in the Figure, a few countries with important undernourishment issues like Kenya or Bangladesh, have benefited from the BSGI to maintain a good supply of wheat, while their overall consumption is still dependent of this commodity.

Other countries like Yemen or Afghanistan present a different type of vulnerability, even though the BSGI is playing a small role, below 8 percent of their overall wheat supply, both countries have very high level of undernourishment and are highly dependent on wheat in their diets, therefore any disruptions could translate in dire consequences for the population.

Other countries like Yemen or Afghanistan present a different type of vulnerability, even though the BSGI is playing a small role, below 8 percent of their overall wheat supply, both countries have very high level of undernourishment and are highly dependent on wheat in their diets, therefore any disruptions could translate in dire consequences for the population.To address this problem, FAO in 2022 proposed a special credit line, known as the Food Import Financing Facility (FIFF) to be extended to low-income countries facing acute food import needs. FAO acknowledges the efforts of the IMF to implement a similar measure and welcomes its decision to maintain this mechanism for six additional months.

The renewal of BSGI will prevent a sharp decrease in agricultural production in Ukraine, which is vital for the world, considering its critical role in supplying oil-seed and grain to the global market. Its suspension in addition to the war, is posing an additional challenge to the farmers due to higher logistics’ costs to export through alternative routes, means and initiatives.

All existing initiatives are more costly with much less absorption capacity compared to the BSGI. The alternative routes would require increased logistical services and its associated costs would have an impact on international prices.

[A graph with different colored circles Description automatically generated]

Second, governments are always encouraged to refrain from using export bans and other trade-restrictive measures, which could contribute to market uncertainty.

There is also a need to take concrete steps to improve the functioning and long-term resilience of global production and markets for food and agriculture, including by reducing distortions, improving capacity and ensuring that efficiency and sustainable productivity will be improved.

This also means strengthening the provision of public goods, for example by improving the availability of extension and advisory services, investing in research, and improving infrastructure in rural areas.

The right investments are needed now to transform agri-food systems to be more efficient, more inclusive, more resilient and more sustainable to deal with the current crisis and build resilience to future crises, while responding to the challenges due to the impacts of natural disasters induced by the climate crisis.

To meet the targets of SDG2 by 2030, agri-food systems must be transformed to enable them to produce “more with less” and technology, science and innovation contributing to the agri-food systems transformation, will be crucial.

Oleksandra Klitina, Kyiv