Fukuyama: What will stop populists, who strengthens Putin and where Ukraine is now

Almost 30 years ago, well-known American philosopher and political scientist Francis Fukuyama predicted that with the fall of the Iron Curtain, liberal democracy would eventually prevail over all other political systems. Although the number of democracies in the world has actually increased by three to four times over these decades, political systems in many countries remain far from being democratic... There was the emergence of populism, which provoked a global democratic crisis, Fukuyama says, explaining the reasons for this development.

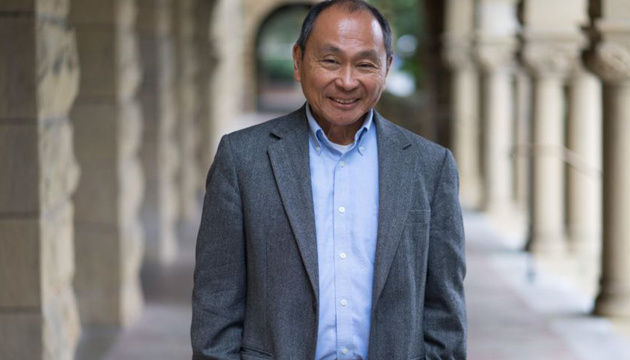

A professor at Stanford University has recently attended Tipping Point Talks, an event organized by the ERSTE Foundation in Vienna. First, he talked to journalists and then he gave a lecture to a wider audience. Ukrinform was present at the event and offers you 13 theses voiced by the American philosopher, including on the topic of Ukraine and Russia's ongoing aggression.

1. The emergence of populism in democratic countries

For most of my life I've been thinking about how we expand the realm of democracy and make more countries democratic, improve their quality, move from authoritarian governments to democratic ones. And then all of a sudden 2016 happened. A number of very disturbing developments occurred that year — the election of Donald Trump as president of the United States and the Brexit vote in Britain to go out of the European Union. And this came against the backdrop of a really changing global environment.

So for the last 30 years since 1989-1991, we have been living in a growing liberal international order. This has been put together largely by the United States together with its allies in Western Europe, NATO alliance and the Far East. It had an economic component which was the system of free trade, the movement of goods, people, services, ideas, investment across international borders. And it had a political component which was the alliances of the United States in Europe and in Asia. This was a really, really successful set of initiatives. The number of democracies in this period went from about 35 in 1970 to 115-120, depending on how you measure democracy, by the early 2000s. The global output of the world economy quadrupled in virtually every respect. Economic conditions were getting better not just in terms of incomes, rising middle classes and places like China and India but better child health, infant mortality was going down. All of these things were happening.

And yet all of this reversed some time in the mid and late 2000s. So you have the rise of a couple of very self-confident and authoritarians powers — Russia and China. But from my standpoint, the most disturbing thing was this emergence of populism within established democracies and, in fact, within the two most established democracies — Britain and the United States. And it seemed to me that it was really vital to figure out why this was happening and what was going on because the entire way of democratization looked like it was being reversed.

2. Three forms of populism

I just want to run through three definitions of populism.

The first definition is an economic one. A populist is a leader who promotes economic policies, social policies that are popular in the short run but disastrous in the long run. So, for example, Venezuela where Hugo Chavez and previous presidents opened clinics and gave out free food, gasoline and so on. None of these were sustainable ones - the price of oil collapsed in 2014.

The second definition is more of a political style than anything else. A populist leader tries to be charismatic and says 'I have a direct connection with you the people.' And that's actually quite important because it makes a populist, I think, ipso facto anti-institutional. The populist says: 'I represent you the people and here are all the other institutions, like courts, like the media, like a legislature, bureaucracy, and they all are standing in the way of my ability to deliver to you what you want me to give you. Therefore, a populist goes after all those institutions.

As an example of this, when Donald Trump accepted Republican nomination in 2016, he had this remarkable line and in an acceptance speech he said: "I alone understand your problems and I alone can fix them."

The third definition is that a populist is when they say 'I support the people,' oftentimes they do not mean the whole people. They mean a certain kind of person usually defined by race or ethnicity or oftentimes in terms of traditional cultural values, traditional sense of national identity. And that does not correspond to the actual population that might live in that country.

So, again, Viktor Orban in Hungary has said very explicitly 'The national identity of Hungary is to be an ethnic Hungarian,' meaning 'If you are not an ethnic Hungarian, you are not part of the nation.' And on the other hand, if you are an ethnic Hungarian living outside of Hungary, and there are a lot of them, you are part of the nation.

3. The United States of Europe and national identity

So now I have no problem of principle with the United States of Europe. In fact, I don't think that Europe can make the euro a coherent policy without moving towards that kind of a union. But I also think that at the present moment it's not very realistic.

I think Europe will be lucky to hold on to what it has already achieved. In the economic sphere it's a meaningful degree of unity. Europe can act like a bloc in trade matters and concept policy, talk about things like taxing on Facebook and Google and so further which you couldn't do without being a bloc. But I think on the political side, on the foreign policy side, that is not going to happen. So I think that therefore action on a national level continues to remain necessary.

The other thing is when you think about identity. I think that emotional allegiance of Europeans to national identity is greater than to pan-European identity. And that's another reality, I think, that we are going to confront. Greeks and Germans are different one from another and they don't say 'Yeah, we are brothers Europeans.'

4. Brexit and populism

When we speak about Brexit, there are several possible scenarios. You know, laborists are now sort of endorsing a second referendum. So it's possible they will stretch out negotiations long enough and they can prepare the ground for the other referendum. And maybe Britain will vote to stay in the EU.

So that's one possible outcome but if they can't actually come to an agreement about the Irish border and build the consensus about that deal and they crash out of the EU, it looks like economic consequences are going to be very severe.

I think a lot of Brexiteers argue that it wouldn't be that bad and Britain can do better because it can negotiate bilateral trade agreement with America and China and so on. But none of that, I think, is going to happen.

So it could be an economic pain if Brexit really does happen chaotically. And then everybody will be looking at that and say 'Oh, that's not a good outcome.' So, I think that's the other scenario, by which it's not going to be good for Britain, that can create a new consensus that leaving the EU is kind of a national suicide.

All these populists fantasize about leaving the EU and if you actually see a country that leaves the EU and does really bad, the fantasy disappears.

5. Leftists should push out populists from subject of migration

During the entire controversy over the migrants from Central America Trump is behaving really just shamelessly, exploiting very demagogic issues. But I think it would be good if some Democrat said: 'Yes, actually we do need to enforce our existing migration laws. We can be sympathetic to migrants that are fleeing horrible human rights conditions in Honduras and Guatemala, but we have to do it according to our existing laws on refugees.' But very few Democrats were willing to actually say something like that.

Something similar is, I think, in Europe where relatively few politicians on the left are willing to equivalent statements - that Europe has to be able to control the process of migration. And it's not such a terrible thing if a country is actually worried about who comes to cross its borders and, especially, when it's done illegally. So that's kind of an example of a position that I would want somebody on the left take.

That, I think, would soften that perception among populist voters that the leftists simply are not interested in national borders, nations or rule of law.

6. Populists' threat to EU enlargement

Populists' victory in European elections won't be good because the populists don't like the EU as it is and certainly won't make it bigger. So I think that they would slow down the process.

But, you know, as I was trying to say, that vote won't be the end of the story. Because it's just one vote and it's not probably the most consequential. The EU Parliament votes were never determinative so much.

I do think that the EU accession process is one of the biggest incentives to bring about reforms in all individual countries. And without that attractive poll any kind of moments towards reforms is going to be weaker.

7. About Orban's Hungary

Fidesz Party in Hungary has been gerrymandering districts to make it much harder for the opposition to actually gain seats in the parliament. And most of Hungarian media were taken under control of Orban and his friends. So you have no more playing field for a political competition in future elections, so even if an opposition figure is more popular it may not succeed. So this becomes a self-reinforcing system.

So, I think that Europe has a lot of levers that could be used to push back against this. I believe that some 5% of Hungarian GDP comes in a form of EU subsidies. And this is very annoying because it just helps Orban to supplement his legitimacy even when he is attacking the EU. And the EU doesn't have to do this sort of things.

8. On common European identity

I think that part of the problem with the European Union is that it's not really very democratic at the core. The EU has a lot of power in the European Commission. But the Commission is the least democratic part of the EU, while the European parliament is the most democratic part of the EU and the weakest among all the branches of the EU. So, I think there is a fundamental legitimacy problem when people just don't feel that the EU responds to them. Given the power of the Commission and given its lack of basic democratic accountability, it breeds all this resentment and so further. So I think in the long term the strengthening of the most democratic part of the EU would be one component of that European identity.

But the other part is more a bottom-up sense of identity where if enough Europeans travel, you know the whole 'Erasmus' system of certifying higher education across Europe, it means that more and more European get degrees and study in countries where they weren't born, they marry people from other European countries. I think, over time that is going to create a common sense of being European.

The only problem with that is that it is a very elite phenomenon and a lot of working-class Europeans really don't have the same opportunities to take advantage of the mobility that the EU offers. And so it's going to be in a way that kind of increase in the existing polarization. Because there are some people that benefit a lot from Europe when the others don't benefit. But in the long run more and more people are going to get to know other parts of Europe and there will be something in common.

Even euro. However, I think euro was a big disaster. But even just a common currency does create a certain sense of shared identity. So I think that over time all these things will contribute to European identity.

But it's just going to be a very slow process, particularly when the institutions are designed to promote that.

9. About Putin's ideology and Surkov's 'sovereign democracy'

We had a little conference with Michael McFaul, the former U.S. ambassador to Russia, about this very question of whether Putin represents a new ideology or whether he is simply an opportunist who is using ideas to further his own power and interests.

I think a lot of American surveyors of Russia tend to the latter, that there isn't a really consistent doctrine underlying Putin, and that he is a kleptocrat, meaning highly corrupt, and here his friends are basically interested in protecting their resources and getting more of them.

But I tend to think that he has developed something like an ideology which is based on conservative social principles. This is something he has made a centerpiece of his social program. Opposition to a decadent West that has more gay marriages… What is interesting, that is very attractive to a lot of audiences outside of Russia. So, for example, there's a bunch of conservative Christian groups in the United States who are very close to Russia to push back on gay marriage and promote traditional family values.

The same concerns 'sovereign democracy' ideas that no country should be allowed to tell any other country how to run their system, that no country should be allowed to criticize human rights violations. These are things that many other countries are very sympathetic to.

So I do think that it is hard to call it an ideology because it's not that well-developed but that is a sort of conservative social values that Putin is trying to represent in the eyes of a lot of conservatives around the world. And I think that has given his attempt to project Russian influence and accelerate this projection. He couldn't interfere in American politics unless there were Americans who wanted his support.

I actually met Mr Surkov in the Kremlin probably 10 or 12 years ago. We had a long discussion. He read a couple of my books, and he told me all about 'sovereign democracy.' It seemed like a completely incoherent doctrine that was simply being used to justify whatever Putin wanted to do. But, like I said, I think it's now evolved into a sort of conservative social doctrine that aligns with the Russian authoritarian political system.

10. How to stop Putin's aggression in Ukraine?

I think it's just a continuation of the policy that Europe and the United States followed in terms of sanctions against Russia.

I was actually disappointed with the Kerch Strait incident last autumn that there wasn't a stronger joint condemnation of it and not more pressure put on Russia to lift the blockade of the Azov Sea.

So the question is: 'Can America and Europe sustain that kind of pressure?'

In the case of the United States, we have a very unprecedented policy towards Russia where the U.S. Congress and American bureaucracy - the State Department, the Defense Department – all are very hostile to Russia. They've actually imposed sanctions at the level that [former U.S. President Barack] Obama was not willing to go to. They've provided military assistance to Ukraine. There's only one person who doesn't like this policy, and he happens to be the president of the United States.

It's just that weird situation where the president is completely at odds with his own bureaucracy and doesn't seem to be able to get his way in terms of, you know, expressing his preferences. I do think that there's a real danger in that because, for example, I mean Russia could decide to invade Ukraine, the rest of Ukraine. If I were Putin and I were inclined to do this, this might be a good time to do it when you have a president whose willingness to back Ukraine militarily was questionable. So, I think there are dangers in the current situation.

So it's just like with the EU and the populists. I think that our task now is just to hold on to the existing policy and not to see its weakening. In the EU it's a big problem. Because if Italy and Hungary and other populists do well in the European election, many of them want much more friendly policy towards Russia and that might start to lead to more pressure to lift sanctions.

So I think the best we can hope for is exactly just to keep existing pressure on.

11. Ukraine on frontline of struggle against Putinism

The reason why I spend a lot of time in Ukraine, working with young Ukrainians, as I do, is that I think it's really important for Europe as a whole. Because if Ukraine comes to Putin-style kleptocracy, if it gets back into Russian orbit or if it just simply doesn't get any better, it's going to be a bad sign for a lot of countries in the region.

On the other hand, if it can actually reform itself, deal decisively with corruption, take the right policy decisions that allow its economy to grow, then I think it's going to become a symbol for a more hopeful post-Soviet world, former Communist world. And I don't know which of those outcomes is more likely but I do think it's very important in one way or another because it is a big country and it's a kind of the frontline of the struggle against Putinism.

Vasyl Korotky, Vienna

Photo credit by the author