Nuremberg for Putin, or How to guarantee responsibility for war crimes in Ukraine

In September, Kyiv was visited by Mark Steven Ellis – Executive Director of the International Bar Association, Chairman of the UN-created Advisory Panel on Matters Relating to Defence Counsel of the Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals; a participant in the tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda. His report at an international conference devoted to Russia's responsibility for crimes in Ukraine shows important aspects of this issue. So, it seems, the theses deserve attention and will be interesting to experts and society.

Before talking about responsibility for international crimes, I suggest going back in our thoughts to November 1989. I was in East Berlin then. It was the week that the Berlin Wall fell. Just one night before, Günter Schabowski, the head of East Berlin’s communist party, had unwittingly announced that the border was open. Below, in the streets of East Berlin, an emotional scene unfolded as people swelled towards the border, to cross over into the West. So much was about to change. A door to freedom had opened, and we were on the cusp of a transformation that would soon engulf all of Eastern Europe. It signified the end of the Cold War and the beginning of a “new kind of peace.” In the words of Paul Krugman, it was “one of history’s miracles.”

Nuremberg principles as basis for preventing impunity

The fall of the Berlin Wall also signalled the resurrection of the principle of accountability brought about after WWII. By the end of War World II, the international community had set in motion a lasting and irrevocable effort to enshrine an anti-impunity stance in international law – a concept that remains at the core of international law today in the eloquent form of the Nuremberg Principles.

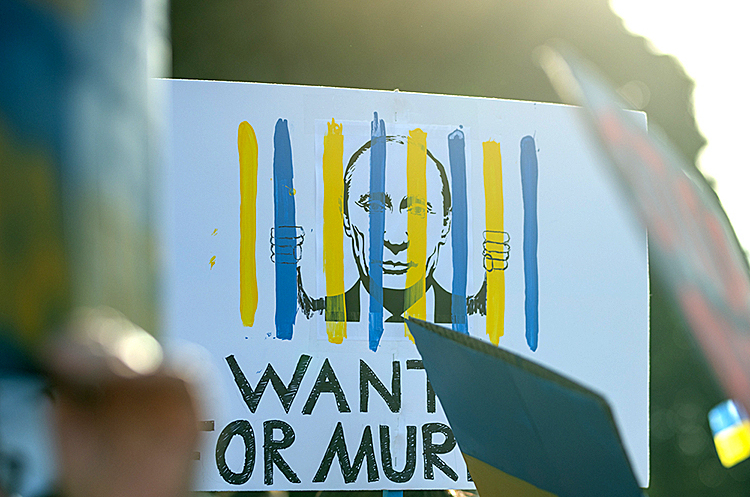

Photo credit: Daily Wire

Photo credit: Daily WireThe principles make clear that: “[t]he fact that a person who committed an act which constitutes a crime under international law acted as Head of State….does not relieve him from responsibility under international law”. Coupled with the prohibition of impunity was a commitment to accountability: “[a]ny person who commits an act which constitutes a crime under international law is … liable to punishment”.

World War II also ushered in a number of accountability mechanisms to ensure there would be no impunity for gross violations of human rights and mass atrocities. A series of conventions followed: the Genocide Convention, the Geneva Conventions, the Convention against Torture, and the prohibition (although not a convention) of crimes against humanity. These conventions are today binding customary international law and mark a legal prohibition on granting impunity for atrocity crimes.

Photo credit: Getty Images

Photo credit: Getty ImagesIn a unique international collaboration, mechanisms to support accountability proliferated with the creation of international, regional, and national war crimes tribunals.

But the golden age of international justice is facing significant challenges. The arbitrary exercise of broad discretionary power by governments—power that is too often aimed at eroding basic human rights – is taking hold. And nowhere this is manifested to such an extent as in Russia.

Russia as biggest threat to world order

In The Open Society and its Enemies, published in 1945, the philosopher Karl Popper warned of totalitarian ideology in the post-WWII period.

The problems he wrote about are now manifest. Russia’s ultra-nationalist agenda as exposed in its war of aggression against Ukraine is the single most danger to the foundation of the international order since WWII.

International law is clear and absolute. A state is prohibited from the use or threat of force against another state. All instances of the use of force by one state against another, regardless of gravity or aims, constitute a violation. This protective principle is inviolable and one of the most fundamental norms of international law. Russia has violated this sacred principle. Vladimir Putin may believe that he is immune from being held liable for these crimes, but he is not. As set forth in Nuremberg, in terms of atrocity crimes, customary international law is now clear – immunity for senior state officials does not exist (certainly for international criminal tribunals). In short, states today continue to advance the position that jus cogens violations of international criminal law do not warrant immunity protection. And because accountability for atrocity crimes is a core component of international law, the international community must work together to ensure those who have committed these atrocities in Ukraine are brought to justice.

There are four ways. Each can be seen as part of a mosaic for accountability

Domestic Accountability and International Criminal Court

The first component of the mosaic is responsibility within the framework of national legislation. With its May 2021 amendments to the criminal code regarding international humanitarian and international criminal law, the Ukrainian Parliament has brought Ukraine’s legislation up to the standards of current international law and the Rome Statute of the ICC. Under the ICC’s complementarity principle, Ukraine can undertake domestic war crimes trials against Russian soldiers who have committed war crimes. Ukraine is doing so and should continue in these efforts.

The second of these four components, which I mentioned earlier, is the International Criminal Court. Russia is not a state party to the Rome Statute and, therefore, on the face of it, is outside the court’s jurisdiction. But, Ukraine, back in 2014, accepted the ICC’s jurisdiction.

Under the Rome Statute, Ukraine was able to, in essence, ask the court to look into any crimes that fall under the Rome Statute and that occurred in Ukraine from 2014 to the present day.

Thus, even though Ukraine is not, in essence, a full state party, the court can still exercise its jurisdiction over crimes committed in Ukraine, by Russia, even though Russia is also not a state party. The distinction doesn’t matter, because the crimes and acts are being committed on the territory of Ukraine that has accepted the jurisdiction of the court.

As you are aware, the Court has opened its investigation. I have no doubt that the Court will issue indictments for crimes being committed in Ukraine. One question that remains is whether the ICC can indict Mr Putin?

This question continues to be a debatable proposition, particularly among scholars. However, if the ICC does pursue Mr. Putin, it will be under the legal concept of command responsibility, which looks at individuals, either in a military or a civilian position, who have effective control over the acts occurring in a war zone and knew or should have known that crimes were being committed and the leader did nothing to stop them nor punish those who committed the crimes.

Someone like Mr. Putin does in fact has effective control over the decisions of military intervention and operations.

So although still controversial I believe the process should move forward toward an indictment against Mr. Putin, or any other Russian military or civilian leader, who had control over the military actions in Ukraine.

The stature of Mr. Putin would undoubtedly see him as untouchable, at least in the short term.

But this is what I always say about this topic: for the types of crimes we are witnessing in Ukraine, there’s no statute of limitations, and there’s no impunity, regardless of one’s position.

Photo credit: Getty Images

In the short term, perpetrators may very well avoid justice. But international justice plays the long game, and because the political atmosphere often times changes, people like Mr. Putin may not be brought to justice in a year or two years, but eventually he will face justice.

There is a history of accountability for political leaders, for example, Slobodan Milosevic and Radovan Karadžić form the former Yugoslavia, Charles Taylor from Liberia, and the former dictator of Chad - Hissène Habré – the first former head of state to be convicted of crimes against humanity by an African Court.

Crime of Aggression and Universal Jurisdiction

The third component of the mosaic of international legal responsibility is the crime of aggression.

Pursuing Mr. Putin for the crime of aggression is generating the most attention.

This is based on the most recent political declaration of the ministerial Ukraine accountability conference. Although there is no direct mention of a tribunal for the crime of aggression, there is a clear acknowledgement that Russia has committed aggression against Ukraine. It is hopeful that the EU/US/UK Atrocity Crimes Advisory Group will play a future role in advocating for such a tribunal.

However, there are challenges to prosecuting the crime of aggression.

Fortunately, like other international crimes codified today, the crime of aggression is embodied in Nuremberg.

The prohibition of aggression is now a jus cogens norm - that is a “peremptory norm of general international law… accepted and recognized by the international community of States as a whole as a norm from which no derogation is permitted.”

The crime of aggression is a leadership crime, meaning it can only be committed by a level of leadership elevated enough to be able to “effectively exercise control over or direct the political or military action of a state.”

Vladimir Putin, as Russian President and Commander-in-Chief of the Russian army, exercises sufficient control to fall within the scope of any crime of aggression definition.

The international community is recognising this reality. In addition to scores of nation-states, The UN General Assembly, the UN Human Right Council, the UN Secretary-General, and the International Court of Justice have all condemned Russia’s act of aggression against Ukraine.

The United Nations (“UN”) General Assembly recently underscored that the unprovoked military attack by the Russian Federation against Ukraine, “on a scale that the international community has not been seen in Europe in decades,” constitutes “aggression… in violation of Article 2(4)” of the UN Charter.

The UN Human Rights Council, in a recent resolution, also strongly condemned the “aggression against Ukraine by the Russian forces.”

The International Court of Justice (“ICJ”) stated in an order on 16 March 2022 in the case of Allegations of Genocide under the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Ukraine v. Russian Federation) that it was “profoundly concerned about the use of force by the Russian Federation in Ukraine, which raises very serious issues of international law.”

Aggression is a crime of singular consequence, because, as the UN Secretary-General observed on 24 February 2022, “the use of force by one country against another is the repudiation of the principles that every country has committed to uphold.”

Over the medium and longer term, work to ensure that there is a jurisdiction ready to demand arrests and initiate prosecutions should be pursued. To this end, Ukraine has already made the creation of a dedicated tribunal for the crime of aggression a core political demand of the international community.

There are several options for such a tribunal:

1. Entering a treaty with a group of states to establish a dedicated tribunal for aggression. A treaty-based tribunal would be international in nature.

As I will discuss shortly, functional immunities for political leaders that arguably apply in national jurisdictions would likely not apply in such an international tribunal.

However, as the Special Tribunal would be created by treaty, not by the Security Council acting pursuant to its Chapter VII authority, it is anything but clear that it would have the authority to set aside the personal immunity of senior Russian officials. The crime of aggression under the Rome Statute recognises this limitation

2. Another option for the creation of such a tribunal would be through a treaty between Ukraine and the European Union, the Council of Europe, or the creation of a European-regional hybrid tribunal.

An EU-supported tribunal would lessen the charges of double standards due to its regional European nature. The EU also has a precedent in the Kosovo Specialist Chambers (“KSC”).

There is already meaningful cooperation between Ukrainian authorities and the European Union, the UN Human Rights Council, including its Commission of Inquiry, the UN Human Rights Monitoring Mechanism in Ukraine, the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the International Commission on Missing Persons, and the Council of Europe

3. A Ukrainian version would include the substantial integration of Ukrainian judges, prosecutors, and other officials. International judges and staff could also be added.

However, I believe that any tribunal must involve other countries as signatories to a treaty presented by Ukraine. The crime of aggression is an international crime and, thus, Ukraine should not be expected to pursue justice on its own.

Finally, the fourth part of this international legal mosaic is universal jurisdiction

Jurisdiction over international crimes can be exercised by international or domestic courts.

Universal jurisdiction is defined as “a legal principle allowing or requiring a state to bring criminal proceedings in respect of certain crimes irrespective of the location of the crime and the nationality of the perpetrator or the victim.”

The rationale for universal jurisdiction is that certain crimes are so critical to the international community at large that states are obligated to pursue justice against perpetrators, regardless of the location of the crime, or the nationality of the perpetrators or the victims.

However, many countries are placing significant restrictions on the use of UJ, requiring a nexus between the preparator of the crime or the victim, and the country pursuing jurisdiction.

Also, sitting heads of state like Mr. Putin enjoy personal immunities from civil and criminal proceedings before other states.

Is immunity of the head of state an obstacle to punishment?

Immunities – A Tale of Caution

In relation to Mr. Putin, one must take into account the application of head of state immunities for the approaches mentioned above.

International law distinguishes personal immunities (immunities ratione personae) and functional immunities (immunities ratione materiae).

The choice of forum for prosecution has significant implications for the application of immunities.

Neither personal nor functional immunities would apply to prosecution by an international tribunal that can be said to act on behalf of the international community( although I suspect this would mean the UNSC). Immunities, including for heads of state, do not apply before international tribunals.

However, both personal and functional immunities will apply in proceedings before foreign domestic courts.

Personal immunities may apply in relation to incumbent heads of state, heads of government, and foreign ministers, and, subject to the exception for international crimes discussed below, functional immunities may apply to all state officials in the absence of a waiver of immunities by Russia.

As immunities would apply in criminal proceedings before foreign domestic courts, it would likely be preferable to work toward establishing an international tribunal with jurisdiction over the crime of aggression, where immunities would not apply at all. Although there are limitations.

Sitting heads of state, heads of government and foreign ministers, enjoy personal immunities from civil and criminal proceedings before other states.

The ICJ clarified in the Arrest Warrant case that the immunities accorded to these persons were not granted for their personal benefit, but to ensure the effective performance of their functions on behalf of their respective states.

Personal immunities cease when the official leaves office. Thus, personal immunities do not bar the prosecution of Mr. Putin before foreign domestic courts once he has left office.

However, until Mr. Putin is no longer in office, personal immunity extends to the issuance of arrest warrants. Fortunately, it does not prevent opening investigations into the conduct of a high-level foreign official.

Functional immunities apply to all state officials for conduct they performed in an official capacity. In contrast to personal immunity, functional immunity is continuing; it does not cease to apply once the official leaves office.

Increasingly though, states recognize an exception to functional immunity for the prosecution of international crimes.

Conclusion

The universality of human rights, territorial protections, liberalism, economic integration, and the fortification of democracy are all under threat by Russia’s war against Ukraine.

However, if there is a positive aspect of this crisis, it is the attention being paid to the ideas of justice and accountability and international law.

Even though Russia is violating the most sacred principles of international law, those actions are galvanizing many other countries that now understand the importance of protecting the principles of international law. They understand that these principles are under threat.

However, I think there is a revelation now, an awareness of the important role international law plays. A greater appreciation and acceptance of the importance of these international principles will hopefully lead us to protect them.

... Conference "Russia's responsibility for crimes in Ukraine: procedures, institutions and role of lawyers. ECHR" was held in Kyiv in September. The organizer of the conference, Systemic Communications Agency, continues a series of discussions about key institutions of international justice with the participation of leading lawyers, diplomats and international experts. We will follow its progress.

Photos taken from open sources