Imperial Russian culture: if you can't cancel it, you have to dismantle it

In our previous articles, we have discussed a large topic - Russian messianism and its place in the system of chauvinistic, rashists views. Now we take up a related topic, a large and interesting one, about which there is a lot of debate.

This is the role of Russian culture and its most prominent part, Russian art, in the formation, consolidation, and reproduction of an aggressive empire.

TO ABOLISH RUSSIAN CULTURE OR PUT IT ON HOLD?

2022 - the liberation of Bucha, Irpin, and other Ukrainian territories. Ukraine and the world witnessed terrible crimes in the places where the occupiers had just been driven out. One of the consequences of this shock was a discussion of how the army, the citizens of a country that boasts of its culture and art, and promotes them as the hallmark of the state, could do this.

And then people started talking about the possibility of boycotting such Russian culture. It was a natural reaction. It was all the more natural because in 2010-2020, democratic countries developed a tradition of ostracizing individuals, works, and phenomena whose view of the world has changed massively. In this regard, a special term has emerged: "cancel culture".

In the course of heated discussions, most Western intellectuals and politicians came to the conclusion that, despite their understanding of Ukrainian pain and respect for Ukrainian grief, this is still impossible. The Minister of Culture and Information Policy of Ukraine, Oleksandr Tkachenko, proposed a more comfortable formulation for our partners: to "pause" Russian culture and communication with Russian figures, at least until the end of Russian aggression. But even this turned out to be too drastic a step for many.

However, there are places, countries, where they are now trying to consistently implement such a cultural policy. This is primarily Lithuania.

But still, it is impossible to either abolish Russian culture or put it on hold on a massive scale, despite all the horrors of the war unleashed by Moscow.

What is possible?

TO STOP UNCRITICALLY ADMIRING THIS CULTURE

In fact, not much is needed: to begin with, stop calling Russian culture "great". In the Ukrainian language, this word carries a more adequate meaning in this case: "great". Yes, as large in scope as all imperial cultures that accumulated in themselves (on the basis of the language and traditions of the titular people) the talents and efforts of many spaces and peoples. With this understanding, the point is not so much in narcissistic "greatness" as in "magnitude." Which is more adequate.

We also need to stop admiring Russian culture excessively, looking at it through rose-colored glasses: exceptional humanism and attention to the "little man," the "mysterious Russian soul," and so on.

It is also important to remember that Russian culture has always been in the same cart as Russian messianism-with its painful expectation and preaching of the special mission of the Russian people and their creations.

So, we simply need to look at Russian culture critically, first of all, from the point of view of the empire it contains. More often than not, it is a naïve, familiar, natural, and therefore unnoticeable empire. And here we must again recall the thesis of the "internal colonization" of Russia, introduced by Russian historians and borrowed from them by other humanities scholars. As Muscovy/Russia pushed its borders further and further away (as a result of conquests - which is often overlooked!), external colonization turned into "internal colonization."

Which, in fact, meant the "digestion" of the spaces and peoples that found themselves abroad. And this was called "Russia" without a shadow of a doubt, since the Russian man and his flag had been here.

Once upon a time, the English, British sailors, traders, and military said something similar about themselves and their country/empire. But that metropolis, that country, grew out of it and reflected on its colonial art.

IMPERIAL REALITIES THAT ARE NOT PERCEIVED AS IMPERIAL

This is not the case with Russia and Russians.

Does anyone, not only in Russia but also abroad, perceive much of the work of the literary founders, Pushkin and Lermontov, as essentially colonial prose and poetry? After all, this is true - according to the historical fact of the current capture and digestion of territories, according to the themes, according to the accents in the description of the relationship between the local population and the conquerors…

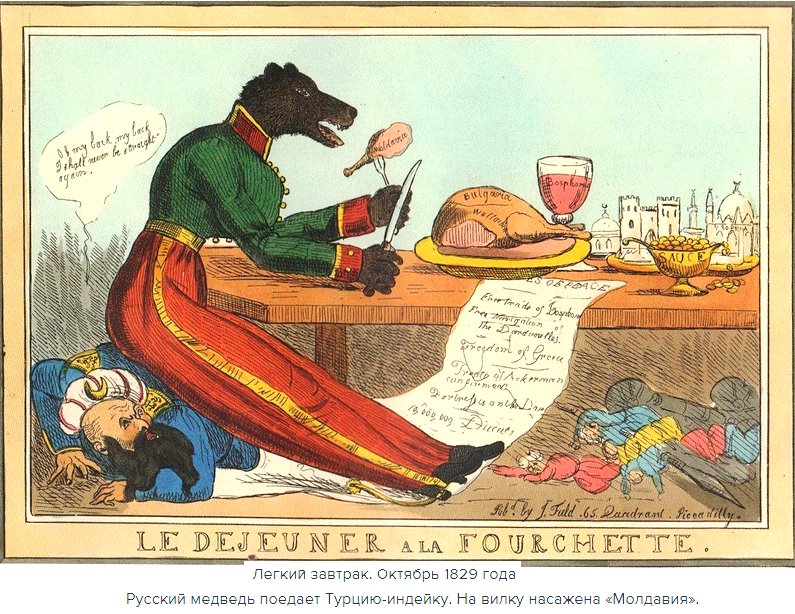

The narcotic outbreak of almost universal happiness, Putin's "Crimean consensus" of 2014, became possible because in Russian culture Crimea is perceived as something legitimately "theirs," moreover, heroically theirs. This is ridiculous and simply impossible to question. What about the Crimean Tatars, Krymchaks, Karaites? "Oh, leave it, it's all so insignificant, just a little local color." The genocidal policy towards the Crimean Tatars, which led to the exodus to Turkey and, under the USSR, to deportation to Central Asia, aroused sympathy among a negligible percentage of Russians.

It is the same with the Caucasian War, which lasted half a century (1817-1864). What is it for Russian culture and Russian art? It is a familiar and, because of this familiarity, even endearing backdrop to traditional Russian life. It tickles the nerves a little if the hero of the story has to go there. Is there any doubt in the Russian tradition that it is righteous, or at least wrong, or at least morally questionable? Almost no, very little. And is there any sympathy for the Circassians, who, as a result of the same genocidal policy, were mostly destroyed or forced into the Ottoman Empire? Practically none. What can we talk about if the perception is that from Novorossiysk to Sochi these are eternally Russian cities. After all, Russia has never attacked, only defended itself...

So, a lot of work is expected in analyzing, explaining, and popularizing knowledge. And this is directly related to our present. After all, the current war began with the occupation of Crimea and the subsequent surge in imperial sentiment in Erephia.

OLD MOSCOW CULTURE AND YOUNG RUSSIAN ART

In everyday life, in journalistic work, and in rubrics, the word "culture" is often synonymous with "art." Although its meaning is, of course, broader. Culture is any manifestation, both tangible and intangible, spiritual, of human activity and human communities.

A reminder of this distinction is important for understanding the age-old difference between "Russian culture" and "Russian art." The orthodoxy of Vladimir-Suzdal-Moscow Orthodoxy, which was as far east as it went, imposed strict restrictions on public life, making secular art and science impossible, even in its humanitarian version.

Therefore, it is quite natural to talk about the ancient traditions of Russian culture. But Russian art in the modern sense and in its various genres-literature, painting, music, and theater-is a very young phenomenon by historical standards (and against the background of other imperial cultures). It can, of course, be extended by chronicles, spiritual writings (or rare excesses, such as Ivan the Terrible's correspondence with Prince Kurbsky). But this is more like a prenatal, intrauterine period of development, or rare exceptions that confirm the rule.

At the same time, Muscovy/Russia has always traditionally recorded ALL works of ancient Russian culture and art in its register, tearing them out of the history of Ukrainians and Belarusians. This unfairly made those "side branches" that have no ancient history. And this is also not widely realized or overcome.

As the Russian propagandist Margarita Simonyan recently said, addressing "Ukrainians and all of them" (i.e., other peoples of the Empire): "Is that what you didn't like about living with us? What was wrong with you? Your statehood appeared for many at the expense of us, your culture as such appeared at the expense of us. Who oppressed you? Who touched you?" By saying "with us" and "at our expense," Simonyan, of course, does not mean Armenians and Armenia, but Russia and Russians.

This kind of arrogance, redefined and made obscene in other countries, is natural and common in Russia, unfortunately, not only among Z-propagandists, but almost everywhere. Therefore, the explanation that various humanitarian knowledge came to Muscovy/Russia from Ukraine, in particular from graduates of the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, puts the vast majority of Russians into a state of stupor, causing distrust or ridicule.

TEENAGE IMPATIENCE IN ART - THE BELINSKY SYNDROME

Generally speaking, the youthfulness of Russian art has made it characterized by a kind of adolescent impatience, a desire to become an adult as soon as possible. To stop imitating and being an apprentice, but rather to feel self-sufficient and great (which, by the way, will allow you to teach others).

Such sentiments are particularly evident in the texts of the "furious Vissarion," the Russian critic of the first half of the nineteenth century, Vissarion Belinsky. "The Russian personality is still an embryo; but how much breadth and strength is in the nature of this embryo, how stifling and terrible is every limitation and narrowness to it," he wrote in one letter.

These words about the "Russian personality being an embryo" are also, by the way, capable of baffling those who like to think about "millennial Russia." But then there is the well-known element of dimensionless narcissism, the expectation of unparalleled greatness that can be achieved by a people with such natural "breadth and strength." But the rejection of "limitations"-what is this about? It is hardly about freedom as such, although Belinsky was considered a "revolutionary democrat." Rather, it seems to be about the non-recognition of "any" restrictions, self-restrictions, which can hardly be considered a positive, constructive quality that should be admired.

The example of Belinsky as the first "revolutionary democrat" on behalf of young art is illustrative of another quality: imperial rejection of otherness, rejection of individuals and peoples who do not fit well into the titular imperial culture. Although not in articles, but in letters, Belinsky spoke exquisite nastiness about Taras Shevchenko and the possibilities of Ukrainian culture, and made racially offensive sketches of Crimean Tatars.

And in this sense, he is a forerunner of the Russian liberals of modern times, who harmoniously combine the self-awareness of a democrat with the arrogance of an imperialist.

BE PREPARED FOR THE CONSTRUCTION OF A LIBERAL EMPIRE!

It is said that when Anatoly Chubais spoke about the need to build a "liberal empire" in 2003 on the eve of the parliamentary elections, it was not so much a call to voters as to elites. And the liberal part of them (unlike the imperial part) was generally ready for this. Is it so?

Not once, but in 2001, not just anywhere, but on Radio Svoboda, a discussion program called "Imperial Culture of Russia: Time and Place" was broadcast. It was attended by authoritative people who described the imperialism of Russian culture not just in an analytically detached way, but in a completely benevolent way.

Here is the historian, critic, and writer Kyrylo Kobrin:

"The government [Russian] played the role of a European, as Pushkin said, not only in relation to Russians themselves, but also in relation to other peoples of the Russian Empire. Here it is appropriate to recall Pushkin's phrase from A Journey to Arzrum, when he reflects on how to solve the Caucasian problem, and he writes that a samovar would be very appropriate here. That is, a samovar as a symbol of a certain civilizing imperial function."

The "Caucasian problem" (and the Second Chechen War was already in full swing at the time) is a soft way of referring to the aforementioned fifty-year-long Caucasian War. But let's not nitpick - it is still about the past, and it is still quite neat.

Here is how the present is described by historian Andriy Zubov. He reflects on whether multi-confessionalism has been formed in Russia (after all, the Chechen war, which the Kremlin waged under the banner of fighting "Islamic terrorism," is still going on):

"It seems to me that it has formed rather than not. Because the fact of multi-confessionalism exists in today's Russia, both in the great Russia, in the Commonwealth of Independent States, and in small Russia, the Russian Federation."

Impressive! It has been ten years since Ukraine and other former "union republics" have been independent, and for Professor Zubov the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) is greater Russia, while the Russian Federation is only small Russia. Despite the fact that Andrey Borisovich is not an imperial dinosaur, but the nicest liberal intellectual who left Mordor after February 24. But, unfortunately, his views were exactly the same: Russia is an inferior, chopped-off, "little Russia."

CONSIDERATIONS ON HOW BEST TO REVIVE THE "IMPERIAL ATTRACTION"

But it gets worse. The interlocutors argue that the imperial culture in the territory under consideration was formed twice and destroyed twice. First in the tsarist version, then in the Soviet one. So maybe it's good that this happened, that we have forgotten, moved on, and are creating something new? No, the reasoning goes in a different direction. And again, Kobrin (who, by the way, left Russia long before 2022 and has since defined himself as a "European writer and historian who writes in Russian"):

"Now it, the Soviet imperial culture, may be partly strong as a memory, but the further we go forward, the further life goes, this memory becomes thinner and thinner, more distant, and eventually it will disappear. The current reality of Russia is that it is not the imperial culture, but the Russian culture itself that can be perceived by other peoples, representatives of other cultures and other confessions. But only depending on their degree of socialization and inclusion in the economic, social, or cultural life of Russia. This is where ORT [now Channel One] and NTV would serve as a 'samovar'."

In other words, in the fall of 2001, when the largest Russian channels had already been seized by the Kremlin, it was they who were proposed to carry "some civilizing functions" to the post-Soviet masses. It has been a year since the Soviet anthem was restored, but it is said that "memories of the Soviet imperial culture are becoming thinner and more distant." Jesus, what planet are these people from? Zubov's proposal is quite different, but also unimpressive:

"The escape from the imperial, which was characteristic in the first years of perestroika, and is still characteristic in many ways, is an escape from the Soviet in general. But the trouble is that the good pre-revolutionary peoples have completely forgotten the good pre-revolutionary peoples, and the desire for imperial unity, not necessarily political, but cultural, persists. It is associated with the Soviet, which is remembered, and in the Soviet, most people remember more bad than good. And I think it's impossible to get out of this paradox without remembering that old pre-Soviet culture, without actualizing it."

Yeah, the problem, it turns out, is that imperialism is associated with Sovietism. And fresh memories of Soviet times are often bad. Therefore, in order to overcome this "misfortune" and strengthen the "desire for imperial unity," it is now necessary to revive the memories of the "good imperial" that existed before 1917.

Again, what planet are these highly educated people of liberal views from? Do they not understand, for example, how Ukrainians have good memories of the "good pre-revolutionary": the elimination of autonomy, enslavement, the Valuev Circular and the Ems Decree? Later, as Putin's policies become more rigid, authoritarian, and aggressive, they will move away from such ideas. But back in 2001, Russian intellectual elites were quite ready to build a "liberal empire," a la Chubais.

This is the end of the introduction to the topic and next time we will begin to consider Russian literature, its role in the imperial state, and the elements of imperialism in Russian literature.

(To be continued)

Oleh Kudrin, Riga