NATO's Collective Defense vs. the Cluster Munitions Convention: A Call for Unified Policy

The CMC, aimed at banning the use of cluster munitions, inadvertently hampers NATO’s ability to defend its members effectively. The CMC was drafted and signed in a drastically different security environment than the one NATO faces today. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, its threats to the wider European security community, and the resurgence of great power competition due to the rise of China demand stalwart leadership ready to dispense with the utopian CMC.

At the Crossroads of Defense and Diplomacy

The conflict between these two international commitments is not merely theoretical. Suppose Russia invades Estonia, Lithuania, Norway, or Poland. In that case, NATO’s Article V will be triggered, and all 32 NATO members will be drawn into the conflict. However, several NATO members, including those like Norway, Moldova, and Lithuania—nations that have been directly threatened by Russia—remain bound by the CMC. Despite recognizing the existential threat posed by Russia, these nations are unable to deploy cluster munitions, a critical tool for defense. Norwegian Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Støre, has openly acknowledged the “more dangerous world” we live in following Russian invasion of Ukraine, and the E-tjenesten (Norwegian Intelligence Service) has similarly echoed that Russia’s war production - much of which is cluster munitions - is a threat to “Norway’s sovereignty, its people, territory, public functions and infrastructure.” Moldovan President Maia Sandu warned in 2023 that Russia could attempt a coup in Moldova if it could by "sabotage and militarily trained people disguised as civilians to carry out violent actions, attacks on government buildings, and taking hostages." Lithuanian President Gitanas Nausėda emphasized "if Russia is not stopped, it will continue to advance, and the front line will be getting closer to us." Yet, despite these dire warnings, these nations and others continue to cling to the belief that they can deter Russia without fully embracing the military tools necessary for effective deterrence.

Russian threats are not without precedent or teeth. Russia has occupied and invaded Lithuania multiple times; in 1795 during the partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, again in 1918 during the Soviet westward advance, in 1940 before the Soviet-German war, and after repelling the Germans, the Russians occupied Lithuania again until the USSR’s collapse. Despite the very real threat of future invasions by Russia, highlighted by Vladimir Putin's remark that "The collapse of the Soviet Union was the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century," Lithuania continues to remain a signatory of the CMC, and is being strong armed by advocacy groups like Human Rights Watch. Despite its decision to withdraw from the CMC with a decisive parliamentary vote of 103 to 141, on August 1, 2024, Mary Wareham of Human Rights Watch stated "Lithuania’s withdrawal will only take effect six months after the documents are submitted to the United Nations and the convention’s States Parties as long as Lithuania is not engaged in armed conflict at that time. Article 20 of the Convention explicitly prevents a State Party that is engaged in armed conflict from withdrawing before the end of the conflict. This hamstringing of a state’s military capability that is evidently aware of both the historical and present threat that Russia represents limits the sovereign decision to withdraw. Furthermore, the inability to withdraw in a timely manner limits Lithuania and states who might withdraw in the future ability to defend themselves in the critical time between an invasion and the employment of these munitions.

This is verbatim from Cluster Munitions Convention: Article 20:

1. This Convention shall be of unlimited duration.

2. Each State Party shall, in exercising its national sovereignty, have the right to withdraw from this Convention. It shall give notice of such withdrawal to all other States Parties, to the Depositary and to the United Nations Security Council. Such an instrument of withdrawal shall include a full explanation of the reasons motivating withdrawal.

3. Such withdrawal shall only take effect six months after the receipt of the instrument of withdrawal by the Depositary. If, however, on the expiry of that six- month period, the withdrawing State Party is engaged in an armed conflict, the withdrawal shall not take effect before the end of the armed conflict.

In the context of a rapidly escalating conflict, this inability to withdraw in a timely manner could result in catastrophic consequences. The time between an invasion and the actual employment of cluster munitions could be the difference between a successful defense and a devastating defeat. For Lithuania, and for any other NATO member that might seek to prioritize its national security over adherence to outdated conventions, this legal straitjacket not only limits their sovereign decision-making but also exposes them to the very dangers the alliance is meant to guard against. It is imperative, therefore, that NATO members reconsider their commitments under the CMC, ensuring that legal frameworks do not hinder their capacity to defend themselves and the broader alliance effectively.

Lessons from the Frontline: Ukraine’s Struggle and NATO’s Challenge

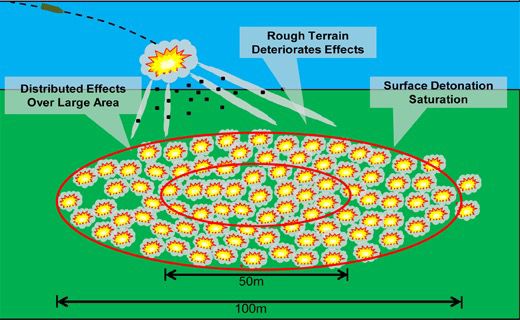

The CMC is even more significant in light of recent events in Ukraine. During the Russian invasion, the West’s legal and moral hesitations over providing cluster munitions cost Ukraine valuable time and lives. It took 19 months for Ukraine to receive a full array of cluster munitions, during which tens of thousands of Ukrainian soldiers and civilians died. If NATO members are required to wait the agreed upon sixth months, the costs may be just as high.

The Ukrainian case demonstrates that these constraints can delay critical military assistance, allowing adversaries to gain the upper hand. In a conflict involving NATO members, such delays could result in the loss of strategic territory, the weakening of defensive lines, or even the failure of a key military operation. The human and strategic costs of adhering to the CMC in such a scenario would be immense, calling into question the wisdom of maintaining such constraints in the face of existential threats.

Legal Warfare by Russia; Undermining NATO from Within

Russia exploits such legal constraints through its strategy of Legal Warfare, a tactic that involves using international law to create divisions and inhibit the strategic operations of its adversaries. This approach is particularly evident in the case of the Cluster Munitions Convention (CMC), where Russian state media, TASS, has reported that the United States is transferring cluster munitions through Germany—a signatory of the CMC. By highlighting this transfer, Russia frames Germany as potentially violating international law, sowing discord within NATO and creating hesitation among its members. Such maneuvers are designed to undermine collective defense efforts by casting doubt on the legality and unity of NATO's military actions.

Historically, NATO has faced similar challenges with other arms control agreements that have limited its capabilities. For instance, the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE Treaty) imposed restrictions on the number and deployment of conventional military equipment in Europe. While the treaty aimed to reduce the risk of large-scale conflict, it also placed significant limitations on NATO's ability to respond swiftly to emerging threats. Russia's suspension of its participation in the CFE Treaty in 2007 further complicated NATO's strategic posture, as the alliance had to navigate the legal and political ramifications of Russia's non-compliance while maintaining its own commitments under the treaty.

Another example is the discord within NATO over the deployment of intermediate-range nuclear forces (INF) during the Cold War. The INF Treaty, signed in 1987 between the United States and the Soviet Union, eliminated an entire class of nuclear weapons. However, the treaty also sparked significant debate within NATO, particularly concerning the deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe. Some member states were reluctant to host such weapons, fearing escalation and the potential for their territories to become primary targets in a conflict. This internal discord weakened NATO's deterrence posture and exposed fractures within the alliance that could be exploited by adversaries.

To counter these tactics, NATO must prioritize unity and clarity in its legal and strategic frameworks. Ensuring that all member states are on the same page regarding the use of specific weapons systems—such as cluster munitions—is crucial to maintaining a robust and effective defense posture. Without such unity, NATO risks being hamstrung by legal ambiguities and internal disagreements, which adversaries like Russia are all too eager to exploit.

Reconciling NATO’s Defense Mandate with International Norms

To address these challenges, NATO must adopt a unified policy on weapons approval and interoperability. Defending Europe with 32 different military forces, each adhering to different weapon bans, is impractical. NATO should establish an official policy recommending all members withdraw from the CMC, following Lithuania's example. To further solidify this unified approach, it is essential that the alliance collectively reconsiders its stance on cluster munitions. NATO should not only recommend that all member states withdraw from the CMC but also unify in endorsing the production, transfer, and deployment of these munitions as necessary defensive tools. By taking a strong, coordinated approach—backed by key members such as the United States, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Finland—NATO can present a united front that prioritizes collective security over outdated legal constraints. This strategy would turn the alliance into a powerful counterbalance to the CMC, ensuring that NATO remains fully equipped to meet the security threats of the modern era.

NATO’s ability to defend its members effectively is paramount. The Cluster Munitions Convention, while noble in its intent, hinders this mission. NATO must prioritize cohesive and robust defense strategies, ensuring all member states can fully participate in collective defense without legal or moral impediments. It is time for NATO to act decisively, ensuring the alliance remains capable of meeting contemporary security challenges.

Dr John Nagl is the Professor of Warfighting Studies at the U.S. Army War College.

Dan Rice, president of the American University Kyiv.

Dr John Nagl and Dan Rice are both West Point graduates and decorated Iraq War veterans. Dan Rice was the major advocate for Ukraine to obtain U.S. cluster munitions.

*The authors' opinions do not necessarily reflect those of Ukrinform's editorial board.