“Hopeless Times”: How Empire Prevented Us from Being Ukrainians

In the modern Russia, Ukrainians, who in 1989 used to be the third-largest ethnic group (more than 4 million), in 2021, were 8th (less than 900,000), even despite the inclusion of the population of the occupied Crimea in the statistics, in which the pace of de-Ukrainization in just 9 years was even more impressive. Not a single Ukrainian-language school has been operating in Russia for many years.

Putin publicly calls Russians and Ukrainians one people, thus denying the latter the right to their history, language, and culture. In the Kremlin’s picture of the world, the “natural” unity of Ukrainians with Russians is constantly hampered by some external forces: the Poles, the Austro-Hungarian General Staff, Lenin, and now, first of all, the collective West.

These are not just Putin’s personal delusions or those of his entourage. The dictator’s public revelations on the topic of Russian-Ukrainian relations have already become a guideline for Russian education and humanitaristics in general.

Moreover, the modern aggressive war of Russia against Ukraine is being waged for the implementation of the most Ukrainophobic ideas of the Kremlin clique to eliminate inconsistencies between expectation and reality — by ruthless transformation of the latter. This is done through destruction and murder, torture and exile, as well as forced re-education. This is a programme of genocide of the Ukrainian nation.

This policy is not new. We have a long experience of the destruction of Ukrainianness during the Russian colonial rule over Ukraine. This is the experience of banning Ukrainian books and teaching, the absorption of the Ukrainian church, the persecution and murder of Ukrainian writers and artists, the deliberate marginalization of Ukrainian culture.

The Russian Empire tried to create a triune Russian people, in which Ukrainians were given the role of an ethnographic branch — Little Russians. In the Soviet Union, the goal of Russification was to create a new historical community — “the Soviet people.” Neither the tsarist nor the Soviet empire left Ukrainians chances for preservation and development as a nation.

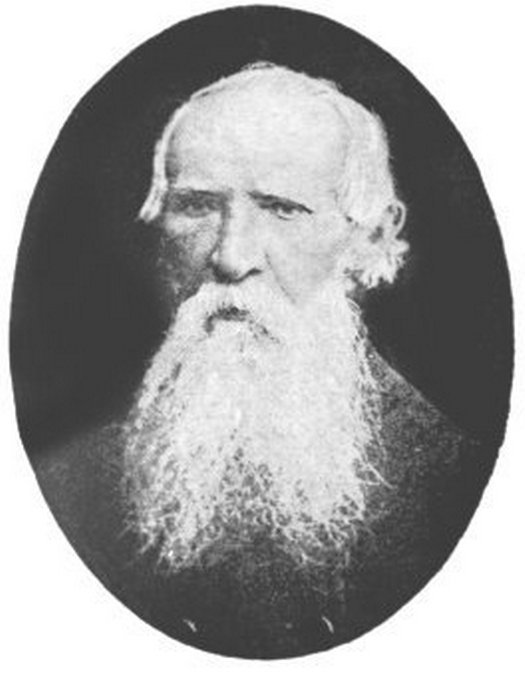

An outstanding figure of the Ukrainian movement of the 19th century, Mykhailo Drahomanov, described the period of Ukrainians’ stay under the rule of kings and emperors (since 1654) as “hopeless times.” The Centre for Strategic Communication decided to recall the main milestones and circumstances of this hopeless time of Russian domination.

Tsarist prohibitions

The agreement of Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytskyi with the Tsardom of Muscovy in 1654 was a fatal historical milestone that set the vector for the development of Ukraine for centuries to come.

How did it affect, for example, Ukrainian book publishing? Its volume began to fall immediately after the subordination of the Metropolitanate of Kyiv to the Moscow Patriarchate — even before all decrees banning the “special dialect.”

Yaroslav Isaevych presents the following data in the book “Ukrainian Book Publishing: Origins, Development, Problems.” In Kyiv in 1652-1675, of the registered 54 editions, 14 were written in the Ukrainian book language, that is, more than a quarter (25.9%). 5 were issued in Polish and Latin, the rest — Church Slavonic. During 1676-1700, only 6 (8.2%) out of 73 editions were in Ukrainian, another 5 were Polish and Latin, all the rest were in Church Slavonic.

After the defeat of Hetman Ivan Mazepa and King Charles XII of Sweden in 1709 near Poltava, the estates of the Ukrainian officers were looted, and their belongings were taken to Russia. The property of the Ukrainian officers, in particular, jewels, as well as the Baturyn archive and much more, replenished the collections of the Russian nobility, which were then just beginning to be created. Probably, during the burning of Baturyn by the Moscow army in 1708, the libraries of Hetman Mazepa and General Scribe Pylyp Orlyk were destroyed by fire.

Since the 1720s, printing in the Ukrainian language and the Ukrainian version of Church Slavonic was completely banned in the Hetmanate. Publishing activities for a long time turned into a simple reproduction of church books in their Russified form due to Russian oppression.

In 1764, Catherine II formulated the basis of a policy towards a number of peoples in a letter to Prince Alexander Vyazemsky: “…Little Russia, Livonia and Finland are the provinces, which are governed by the privileges confirmed by them […] These provinces, as well as Smolensk, must by the easiest means be brought to the point that they become Russified and stop looking like wolves towards the forest. […] if there is no hetman in Little Russia, then we must try to make the name of the hetman disappear forever, let alone the person who was awarded this position…”

Since then, these guidelines for the Russification of Ukrainians were implemented for centuries: both in the times of tsarist Russia and the communist Soviet Union. They caused irreparable damage to the development of national culture, distinctiveness, and identity of Ukrainians. The empire tried to force the most talented ones to the imperial capitals and assimilate them. The most disobedient were to be destroyed and their memory disgraced.

A vivid example of embedding in the imperial system is the then Kyiv-Mohyla Academy. This educational institution, for a long time, was beyond competition among the subordinates of Muscovy and made a tremendous contribution to the dissemination of knowledge from Kyiv to its new metropolis. Theophan Prokopovich studied and taught there, who became a leading ideologist at the court of Peter I. It was he, among other things, who proposed to rename the Moscow kingdom as the Russian Empire and assign to this state the historical “brand” of Rus, which originally related the lands around Kyiv.

In 1784, the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy was ordered to deliver lectures in Russian “in compliance with the accent, which is observed in Great Russia.” In the same year, the Synod ordered Metropolitan Samuel of Kyiv and Galicia to conduct services in all churches “with the voice peculiar to the Russian language.” In 1817, the Academy was closed.

In the nineteenth century, the empire actively encouraged the assimilation of Ukrainians, multiplying the titular Russian nation at the expense of their demographic and intellectual resources.

The pace of Russification at that time was hampered by the fact that the majority of Ukrainians were peasants, over whose life and consciousness the state had limited influence. The Russian upper classes were arrogant towards such common people. Prince Dolgorukov, Vladimir’s governor, wrote in his notes on the visit to Ukraine in 1810: “The Khokhol would be difficult to distinguish from the Negro in all respects: one sweats over sugar, the other over bread. May God bless both of them.”

The Russian nobility perceived socially close Ukrainians as “little Russians,” ethnically related to them. They also served the empire and assimilated into all-Russian culture, sometimes retaining a nostalgic attachment to the “small homeland.”

But contrary to the plans of St. Petersburg, the untouched identity of the uncultivated peasants, and the nostalgic and romantic experiences of the Little Russians from the upper classes collided and launched a powerful national revival of Ukrainianness, which acquired cultural and later political forms. Sensing danger, the empire began to stigmatize conscious Ukrainians as “Mazepynets” and persecute them in every possible way.

Historian Kyrylo Halushko notes: “The national movement of Ukrainians, the largest group of the empire after ethnic Russians, directly threatened the integrity of the Russian nation. This was the reason for the particularly brutal persecution of the activities of Ukrainians relating to language and culture.”

Halushko believes that Russian identity was based on the fight against Ukrainianness: “the conviction of the need to assimilate Ukrainians was fundamental to the very image of Russia and Russians in time and space.”

Of course, the chances in the confrontation, with the education system, privileges, and the entire administrative apparatus of the empire on the one hand, and the sole enthusiasm of the few people’s educators on the other, were not equal. Many of the leaders of Ukraine fell under the flywheel of repression, for example, Taras Shevchenko, who was repeatedly arrested and punished with exile.

Having not yet been able to cover the Ukrainian village with its influences, Russification began with the cities. Gradually, they became foreign islands in the middle of villages, in which the vast majority of Ukrainians lived at that time. The imperial school and the army tried to force Ukrainian peasants to speak Russian, so did the vacancies in cities that needed a lot of labour.

After the death of Nicholas I in 1855 and the Crimean War lost by the Russian Empire (1853-1856), a certain liberalization began. The Polish uprising of 1863 and another wave of Ukrainian revival were motivated by new hopes for freedom. In the imagination of the imperialists, these movements were directly related to each other. The response of St. Petersburg was the Valuev Circular, which prohibited the publication of religious and educational books in Ukrainian.

The history of this act reflects the zeitgeist. According to scientist Hryhorii Samoilenko, in autumn 1860, writer Pylyp Morachevskyi from Nizhyn completed the translation of the Testament into Ukrainian and sent it to the Russian Academy of Sciences to obtain permission of the censorship for publication. However, in 1863, a denunciation came from Kyiv to the name of Prince Dolgorukov, which noted that “Ukrainophiles” were very interested in printing the Testament in Ukrainian, who “to this cornerstone… will attach the isolation of the language, then life, then nationality… We consider it needless to prove that the translation of the Word of God into a miserable Little Russian dialect is a political venture.”

The case of the translation was entrusted to the Minister of Internal Affairs Valuev and Ober-Procurator of Synod Akhmetov. On July 8, 1863, the same secret circular was issued with the now widely known phrase: “There was, is not and could not have been a separate Little Russian language.”

Paradoxically, works of art “belonging to the field of fine literature” were allowed to be published in the language, “which does not exist.” The circular began with the words (here in translation): “For a long time, there have been disputes in our press about the possibility of the existence of independent Little Russian literature. The reason for these disputes is the works of some writers, who are distinguished by more or less notable talent or originality.”

If in 1862, 40 Ukrainian books were published in the Russian Empire, then during 1863 — only 15, and in the following years — only a few books.

Separately, the circular prohibited the printing of textbooks. The importance of the role of the national intelligentsia in education is evidenced by the fact that Taras Shevchenko issued a Ukrainian ABC book for Sunday schools at his expense before the Valuev Circular. It was printed in a large edition at that time of 10,000 copies. Shevchenko collected money personally, “for a donation,” having put up his portrait for the lottery. Although the textbook underwent formal censorship, Metropolitan Arseny, to whom activists sent 6,000 copies of the “ABC Book” to Kyiv, ordered to destroy the edition after consulting the government.

In 1862, Valuev banned Sunday schools, and some Ukrainian educators were arrested and deported to Siberia.

Already in the next decade, in connection with the emergence of influential pro-Ukrainian organizations “Hromady” (Communities) and the South-Western branch of the Russian Imperial Geographical Society, a sharp polemic broke out in the pages of the then press with supporters of the project “united and indivisible Russia.”

This led to the appearance of the Ems Ukase of Emperor Alexander II on May 30, 1876. The title of the decree comes from the place of its signing: in the German city of Ems. The decree prohibited the publication of any books in Ukrainian, except for historical documents, ethnographic materials, and censored works of art.

Particular attention was paid to the education system. Teachers who sympathized with the Ukrainian case were ordered to be evicted deep into Russia. Here are a few excerpts from the Ems Ukase:

– “To strengthen supervision by the local educational authorities to prevent the teaching of any subjects in the Malorussian dialect in the primary schools.

– To pay serious attention to the staff of teachers in the educational districts of Kharkiv, Kyiv and Odesa, demanding from the curators of these districts a personal list of teachers with a note about the reliability of each in relation to Ukrainophile tendencies and to transfer to the Great Russian provinces those noted as unreliable or dubious, replacing them with the natives of these lands.”

– “Not to tolerate persons with an unreliable way of thinking in educational institutions, not only between teachers, but also between students.”

– “It would be useful to take as a general rule that the educational institutions of the districts of Kharkiv, Kyiv, and Odesa appoint mainly Great Russians as teachers, and distribute Little Russians to educational institutions of St. Petersburg, Kazan, and Orenburg districts.”

The theatre was also banned:

“To prohibit uniformly all scenic performances, texts for music sheets, and public readings (as having at present the character of Ukrainophile manifestations) using the very dialect.”

The Ukase also resulted in the liquidation of the South-Western Branch of the Geographical Society and the closure of “Kyiv Telegraph,” the bilingual newspaper of “Hromady.”

The Valuev Circular and the Ems Ukase actually became invalid only as a result of the 1905 revolution. However, books, newspapers, and magazines were then banned for their content.

The publication of the Ukrainian press began again, but its censorship was especially severe. Thus, at the end of 1905, the first Ukrainian-language newspaper Khliborob (grain grower) was banned in the territory of the Russian Empire, which was published in Lubny, in Poltava Oblast. In 1906, the newspaper Free Ukraine was banned in St. Petersburg, Good Advice and Zaporizhzhia were banned in Ekaterinoslav (now the city of Dnipro), People’s Business — in Odesa, Slobozhanshchyna— in Kharkiv.

In a month — from December 1905 to January 1906 — in Kyiv alone, 74 criminal cases were opened against the editors of local newspapers. A typical accusation against Ukrainian newspapers was “propaganda of separatism.” During the World War I (1914-1918), the publication of books in Ukrainian in the Russian Empire was banned again.

As for the theatre, its ban by the Ems Ukase was revised as early as 1881, when plays would be allowed in Ukrainian or Polish, but only if prior to that, the same performance would be conducted in Russian.

Prohibitions and repressions caused considerable damage to the natural development of the Ukrainian nation in the Russian Empire. In contrast, in the Ukrainian lands under the domination of Austria-Hungary (Eastern Galicia, Northern Bukovyna, and Zakarpattia), where there was no such persecution of Ukrainians by the state authorities, the local population reached a high level of national consciousness in the early 20th century.

Galicia even got the title of “Ukrainian Piedmont.” (An analogy with the region from which the national unification of Italy began.) It was not that, according to the Kremlin, some anti-Russian forces deliberately instilled Russophobia in the Galicians. It is just that under the rule of Vienna, Ukrainians developed more freely and organically than under the constant assimilation pressure of the Romanov empire.

Soviet Terror

Despite all the obstacles that St. Petersburg exerted on the development of the Ukrainian nation, not only did it survive, but it also found the potential for state-building.

After the fall of the empire, Ukrainians founded their own representative organization — the Central Rada, which later became the parliament of the Ukrainian People’s Republic (UPR), proclaimed in November 1917.

If Ukrainians followed the path of democratic, republican development, then in Russia, the Bolshevik extremists won. Like their tsarist predecessors, they used their forces to conquer and hold Ukraine under control.

In February 1918, during the first Ukrainian-Bolshevik war, the Red detachments captured Kyiv for the first time. The occupiers immediately launched a bloody terror. Kyiv residents were shot, even for personal documents issued by the Ukrainian authorities, found during the search.

The idea of the mood of the Bolsheviks is conveyed by the words of Mikhail Muravyov, who led the assault on the capital: “We are going to establish Soviet power with fire and sword. I occupied the city and hit the palaces and churches… without mercy! … We could have stopped the wrath of revenge, but we did not because our slogan is to be merciless!”

After several years of bloody struggle, the Bolsheviks managed to finally capture most of Ukraine and destroy the UPR. The defeat and loss of statehood became a harbinger of future catastrophes for Ukrainians.

Many prominent cultural figures died at the hands of the occupiers and Chekists during the struggle for independence. For example, the composer Mykola Leontovych, the author of the Shchedryk, which later became world-famous in the West as Carol of the Bells. A Chekist bullet killed the genius in January 1921.

A significant part of the Ukrainian intelligentsia and patrons of culture were forced to leave their native land, fleeing from class and national terror.

Soviet power was not only much crueller than the tsarist, but also much more insidious. The Bolsheviks quickly realized that it was impossible to keep Ukraine, denying its right to exist (as their rivals from the Russian White Army did). Thus, they began to play to Ukrainian national feelings and use them to gain support and power.

The price of the new enslavement of Ukraine for the Communists was the declarative recognition of the national identity of its people and its right to statehood in the form of a “socialist Soviet republic.” Thus, Lenin did not create Ukraine, as Putin believes. The Bolsheviks realized the strength of the national movement and made a compromise with it.

A vivid phenomenon of the 1920s was the Soviet “Ukrainization,” which was marked by a great rise in literature, theatre, art, and other spheres of culture. What were its reasons? Firstly, as already noted, the Bolsheviks made a compromise to maintain power. Now this power had to be strengthened, lulling the vigilance of anti-imperial forces. Pretending to be the Ukrainian power, the power of the Bolsheviks gradually became more and more ubiquitous.

Secondly, the occupiers of Ukraine were forced to continue competing for influence on the masses with national forces that found themselves in neighbouring countries or in exile. By branding the trident and the blue-and-yellow flag, the Communists tried to prove that they were even greater Ukrainian patriots than emigrants.

These attempts were not in vain. A short period of national revival in the Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic became a magnet for exiles from abroad. They believed in the Soviet Ukraine, began to return. It was at this point that the Bolshevik insidiousness manifested itself. Gathering Ukrainians and allowing them to jump into the whirlpool of creative rise, the totalitarian state began to terrorize.

This short period later received the apt name Executed Renaissance. In 1937, 265 prisoners of the Solovky camp were executed in the Sandarmokh tract in Karelia; most of them embodied the elite of the then Ukraine: politicians, scientists, writers, artists, priests, peasants. This is just one of the episodes of the Great Terror against Ukrainians.

Among those killed was, in particular, writer Antin Krushelnytskyi, former Minister of Education of the UPR. In May 1934, he, like hundreds of others, believed in Soviet Ukraine and returned from Poland to the USSR. In October, he and his family were arrested.

Antin Krushelnytskyi, together with his sons, school teacher Bohdan and university teacher Ostap Krushelnytskyi, were shot on November 3, 1937 in the Sandarmokh tract. The daughter, Volodymyra, doctor and publicist, was convoyed from Solovky and killed a month after her brothers and father. Three years earlier, another two sons of Krushelnytskyi, 29-year-old Ivan, artist and poet, and 25-year-old Taras, writer and translator, were shot by Chekists in the basements of the October Palace in Kyiv.

The fate of the family was later described by Krushelnytskyi’s granddaughter Larysa in the book “Cut-Down Forest.” She herself was taken to Kursk at the age of 6, but her relatives were eventually able to return her to Lviv.

An idea of the scale of Stalin’s terror and the Executed Renaissance is given by the calculations of the Union of Ukrainian Writers Slovo(organization of Ukrainian writers in emigration). Thus, in 1930, 259 Ukrainian writers were published in the USSR, and after 1938 — only 36 of them, that is, 14%. 223 writers “disappeared.” Of these, according to the organization, 192 were shot or sent to camps with possible subsequent shooting or death, 16 went missing, 8 committed suicide.

For other authors in the USSR, there was a ban on the publication of their works. Another part of the cultural figures adapted to the service of the Bolshevik party.

The Holodomor in 1932-33 became a crime and tragedy of universal scale. Because of the artificially created famine, 3.9 million Ukrainians died, mostly peasants — custodians of folk culture, whom the Romanov Empire could not turn into Russians.

After the World War II, the Russification of the school, the press, book publishing, theatre, and television continued. Ukrainian culture became a folklore exhibit in the Soviet Museum of Peoples’ Friendship. Like everything else in the USSR, this friendship was pure pretence, insincerity.

Meanwhile, the processes of urbanization, natural for society, continued — the movement of people from villages to cities. The cities were no longer small islands, as a century ago. They became home to most of the Soviet Ukrainians. But the Russian language prevailed almost everywhere in the cities, and Ukrainian was perceived aggressively and with contempt. Russians and representatives of other peoples of the USSR moved to Ukraine, especially immediately after the World War II, when the restoration of the devastated republic was in great need of workers. This is how Russification intensified.

In the sphere of office work, production, and education, the Ukrainian language gradually became a rudiment. In 1958, parents of students were allowed to refuse to study it at school. Many indeed decided not to waste precious time on lessons of socially non-prestigious language, which seemed to be an endangered relic of the past. Often, children of Ukrainian-speaking parents spoke Russian at home.

Terror did not cease. A new large-scale wave of arrests of the opposition Ukrainian intelligentsia took place in 1972. The detainees were intimidated by shooting, torture, punitive medicine, and causing harm to their relatives. Many were sent to camps. The flywheel of repression affected the poet Vasyl Stus, who, after repeated exile, died in prison in 1985.

In 1974, the party proclaimed the creation of a “new historical community” — the Soviet people. It seemed that in a short time, the dream of the Russian emperors would come true: Ukrainians would finally assimilate and become Russians.

Yet, as in tsarist times, the Ukrainian language and culture survived. The Soviet Union collapsed, and Ukrainians restored their statehood. In the years that have passed since, we have observed that the guarantees of the preservation of identity and the prospects for cultural progress are best ensured by our independent state.

This was also confirmed by the Kremlin, which initially expected to control Ukraine through the so-called “single cultural space.” Over the years, this common space has been constantly narrowing, and control over the tastes and preferences of Ukrainians has weakened. Without administrative instilment, the imperial culture in Ukraine was rapidly losing its positions.

Therefore, Russia fell back into its old ways. As the invaders try to cleanse everything related to Ukraine in the temporarily occupied territories, it becomes clear what future the Kremlin prepared for the whole of Ukraine. But the successful days of empires passed irrevocably. We will not allow ourselves to return to the “hopeless times.”

Centre for Strategic Communication and Information Security