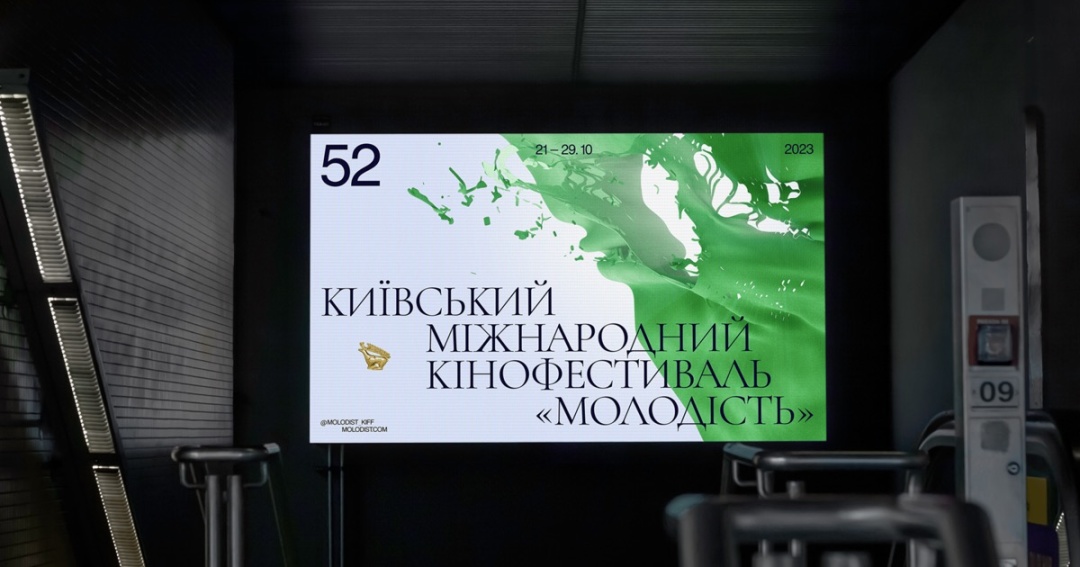

Molodist 2023: Ghosts of distant dictatorships, voices of close front

The 52nd Molodist International Kyiv Film Festival, held in October for the first time since 2016, reminded us of the festivals before the full-scale invasion with its rich program and the number of visitors, while presenting films about the most important issues of our time.

Long before the pandemic and the full-scale invasion, which shifted the timing of almost all domestic cultural events, the management team that took over Molodist IFF moved the festival from late October to late May, announcing that spring weather and the influx of tourists on City Day would help attract an audience. Not only for the experienced Molodist staff, but also for festival regulars, the fatal prospects of such a time jump were quite obvious. However, the warnings that good weather is not an ally of film screenings, but their rival, that tourists will go to Khreshchatyk, museums and churches instead of cinemas, that Molodist will be left without the films of the Cannes Film Festival that takes place during the same period (and without the filmmakers who participate in it), and, most importantly - that such a postponement would exclude the target audience, the students of film faculties who were busy filming their term papers and diploma theses in May (and all other students with them) - these warnings were not heeded, and in 2017, instead of a full-fledged festival, a shortened "weekend" version was held with the announcement of the May Molodist.

The consequences are well illustrated by the statement of one film critic who, when he visited Molodist in May 2018, expressed surprise at the position of his colleagues who opposed the transfer: "Don't you like watching movies in an empty hall?" As predicted, Molodist was left not only without a student audience, but also without foreign guests, and the Kyiv City Hall, which had pompously promised the festival all kinds of support for the transfer to the City Day, soon terminated the contract with the tenants of the Kyiv Cinema, its main venue, after which it ceased to operate.

However, Molodist, thanks to the entrepreneurship and dedication of its organizers, led by Andriy Khalpakhchi and one of the best national programming teams (Ihor Shestopalov, Viktor Hlon, Bohdan Zhuk), managed to survive not only the "marketing improvements" and arbitrariness of the city authorities, but also the hardships of the pandemic and the trials that fell on the Ukrainian film festival process as a result of Russian aggression.

This year, the 52nd festival was held in October, the usual October dates for several generations of moviegoers, with many young viewers who were finally able to take advantage of student passes, films from the Cannes Film Festival competition programs, foreign jury members and film crews, who dared to come to a country at war, and, fortunately, with a minimum of delays due to air raids, unlike last year's festival, which took place at the height of the December terrorist attacks on Ukraine's energy infrastructure by the Russian Federation.

Judging by the intense program, the organizers have successfully adapted to the conditions of wartime. Not only traditional competitions were presented, but also a very powerful competition for debut documentaries, which was introduced for the first time in 2021. In almost all the works of the documentary competition, created in different parts of the world and dedicated to different epochs and the cataclysms that accompanied them, from the Holocaust to the Balkan wars, the drama of great history was conveyed through the experience of ordinary people, witnesses and participants in tragic and heroic acts. The Norwegian film Eclipse by Natasha Urban, which received a special mention, is structured as a journey of the director, who once emigrated from war-torn and militaristic Serbia, through her native land and the waves of her memory, as well as the memories of her loved ones. The stories about the solar eclipses in Yugoslavia in 1961 and 1999 and the newspaper hysteria with pseudoscientific fabrications that accompanied the phenomena serve as a symbolic parallel to the eclipse of collective consciousness that befell the people of the disintegrating country. "Eclipse" shows what disasters are fraught with the policy of silencing the crimes of the past and their distorted interpretations for the purpose of "patriotic" propaganda.

The winner of another award, Anhell69 by Colombian Teo Montoya, is an original combination of documentary and fiction. The author of the film, a native of Medellín, one of the criminal capitals of modern civilization, tells us about his intention to make a sci-fi thriller that bizarrely reflects the reality of a Latin American country that has been plunged into the horrors of civil war, far-right dictatorship and the omnipotence of drug cartels for decades: In a dystopian metropolis, young people with a special psychic sensitivity that allows them to capture the bizarre existence of ghosts enter into romantic relationships with them, but the tyrannical government outlaws sex with the dead and sends paramilitary gangs to hunt down those who disobey. The viewer is shown fragments of the director's interviews with the young men who came to the casting, who, like Montoya himself, represent the bohemian LGBT community, which, according to local conditions, is more often than usual targeted by extremists and ordinary gangsters and is affected by the drug epidemic. As it becomes clear in the course of the story, when work on Anhell69 began, all the young people who appear in the film-including the lead actor, whose Instagram handle is included in the title-were already dead, victims of brutal reprisals or overdoses. Intended to embody the images of sensitive lovers who dared to have a forbidden relationship in the project, they themselves turn out to be the ghosts of Medellín, who now tell their surviving brother about their lifelong hopes and fears, about their thirst for love in a world of hatred and intolerance.

The competition was won by Crossing Borders by Lesia Kordonets, a Swiss filmmaker of Ukrainian descent, about the Ukrainian Paralympic team as it prepares for the competition when war intrudes. Filmed before the full-scale invasion, the film offers a vivid retrospective of the Russian-Ukrainian war, presented through the eyes of the athletes and the leaders of the Paralympic Committee, who, like most of us, did not immediately realize the scale of the cataclysm. And while some of the film's protagonists have been ready to resist the aggressors as much as they can since the beginning of the Russian invasion of the Crimean peninsula (like the Crimean Paralympians who refuse to cooperate with the occupation administration that offers them to join the Russian national team), others are only gradually realizing the nature of what is happening. The film Borderline shows that, just like the physical limitations that the protagonists courageously overcome, the injuries inflicted on Ukraine by the foreign invasion harden the will of our fellow citizens, encouraging them to show mental fortitude and the ability to help each other.

It is quite natural that the audience's sympathies were also attracted primarily by films about the events of the Russian-Ukrainian war - it was the films dedicated to this topic that were among the three winners of the international competition according to the audience vote. Eva Strelnikova's feature film Stay Online, which took third place, became the first Ukrainian example of the screenplay genre and the first feature film to be made since the beginning of the full-scale invasion. The story about the last days of February 2022, which unfolds almost entirely on the monitor screen, in social media correspondence and video calls, which are constantly intruded by news messages, successfully conveys the experience of many of our fellow citizens who spent the first weeks of the Invasion practically never leaving their monitors and never letting go of their mobile phones, trying to find out the latest news, provide all possible help, and make sure that their loved ones are okay. However, the television background of the authors of Stay Online did not have the best effect on the authenticity of the events on screen, and despite the use of an innovative genre and topical issues, the film often seems like an episode of a domestic TV series due to the persistent injection of emotions and excessive sentimentality.

Instead, the work that took second place in the audience voting, Voices from Bakhmut by Ihor Babayev, which participated in the professional shorts section and received a special diploma at the national competition, is truly convincing. It is easy to mistake Babayev's film for a documentary: its visuals are based on photographs and footage from Bakhmut besieged by Russians, and the voice of the fictional narrator, who remains off-screen recording the English-speaking voices messages to their distant lover, truthfully conveys the emotions of a military journalist, whose fascination with interesting material and professional courage are inseparable from empathy for people whose normal lives have been swept away by a military cataclysm. At the same time, both the journalist's passion and compassion for others are sometimes overshadowed by an overwhelming longing for a person with whom a relationship apparently proved impossible not only because of the distance that separated them.

The Audience Award, as well as the award for the best film in the student section of the international competition, went to Alla Savytska's documentary Tutti, which focuses on the attempts of the Kyiv Children's Choir "Shchedryk" to continue their rehearsals after the start of the full-scale invasion. Their rehearsals in the bombed-out Ukrainian capital culminate in a triumphant performance at New York's Carnegie Hall. As in Lesia Kordonets's Crossing Borders, Tutti shows the socio-political catastrophe through the activities of a band that is desperately adapting to the new conditions. However, Savytska's film lacks such expressive portraits, and the choir members hardly ever get solo parts in the story.

A documentary film also won the national short film competition, though it was dedicated to an earlier time. "The Questionnaire" by Natalia Ilchuk is edited from archival footage from the mid-2000s, which captured Natalia in the circle of her fellow students, at night gatherings, walks, and family feasts. Seemingly optional fragments of the author's leisure time gradually develop into a disturbing image of young people gaining sensory experience, their attempts to understand the world around them and themselves, young people who at some point seem to stop at a crossroads with their country, which is frozen at the threshold of formidable changes.

It is worth mentioning another Ukrainian film that participated in international competition and, although it did not win any awards, became one of the most discussed-and most warmly received-films of the 52nd Molodist. At the same time, Maryna Vroda's long-awaited feature debut Stepne (as well as her first professional work Cross, which also won the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival in 2011 for Best Short Film) was recognized at a prestigious foreign platform - the film won the Best Director Award and the FIPRESCI Prize at the Locarno International Film Festival. This film, created before the full-scale invasion, seems at first to be extremely far from the cataclysms of today, but as the seemingly uncomplicated, unhurried action unfolds, it turns out to be a real monument to the tragedy of national history. The central character of Stepnoy, an elderly engineer (Oleksandr Maksyakov), comes to his native village to take care of his sick mother (Nina Antonova), and seems to be witnessing the last days not only of his loved one, but also of Stepnoy himself. In this Sumy village, whose inhabitants seem as decrepit and fragile as the buildings that have survived, it is as if the last act of the tragedy of collectivization, which once destroyed the centuries-old peasant way of life, is unfolding, only to sink into oblivion along with the last of its surviving witnesses and victims. The central scene of the film, in which the villagers gather to remember the protagonist's late mother, telling about their long and joyless life, the war, famine, and decades of hard work and poverty, is perceived as a wake not only for one of the locals, but for an entire era that has remained unreasoned and unmourned. The mutual attraction between the protagonist and his charming neighbor (Radmila Shchogoleva), which seems to be able to finally fill this fading space with passion, is doomed to remain unrealized - this tree will no longer bear good fruit.

The international competition featured many films that responded to the political problems of our time, among the best of which are the French Voices of Others by Fatima Kaci (Student Section Diploma) about a Tunisian native who, working as an interpreter during interviews with refugees by French officials, tries to covertly adapt the refugees' confusing monologues to official requirements, and the Turkish Things We Didn't Hear, by Ramazan Kilich (Best Film in the Professional Shorts section) about a Kurdish settlement that was left without Kurdish-language TV channels by a Turkish military raid - the little heroine of the film finds a way out, by gathering her neighbors for evenings in front of a frame that simulates a TV set, where she reads local news and her fellow villagers perform folk songs and stories (a poignant and funny reminder that the thirst for information and love for one's native language will overcome any oppression).

In the feature-length section, most of the films dealt with the theme of growing up in one way or another, and the films dedicated to this issue won the program. Zeno Graton's Paradise Lost, which won the award for best feature film in the competition, is set in a juvenile correctional facility, where the inmates are trying to find a "golden mean" between the demands of society, the interests of their neighbors and the realization of their own inclinations. For its two central characters, this search and the acquisition of inner freedom, despite unfavorable circumstances, is supposedly helped by mutual sensual passion, but gradually the emotional impulses of the young men get out of control. The somewhat melodramatic tone of the narrative is redeemed by the organicity of the young performers and the sympathetic portrayal of the prison administration, guards and educators, who, in the authors' portrayal, do not resemble stereotypical images of callous and hypocritical tyrants and sincerely seek to ease the difficulties of socialization for their wards.

The winner of the Scythian Stag for Best Film of the Molodist section was the French-Belgian film Dalva by Emmanuelle Nico, about a 12-year-old girl who has been sexually abused by her father for several years. After her father's arrest, and in a shelter for children from disadvantaged families, Dalva defends the notion that what happened to her was nothing wrong, and that those who would convince her otherwise are liars and hypocrites. While continuing to dress like an adult woman, following her parents' instructions, the girl indignantly rejects the arguments of social workers and refuses to see her mother, from whom she was once abducted, convinced that it was her mother who abandoned her and her father. The girl's difficulties in perceiving the real state of affairs can be interpreted as a metaphor for the painful realization of a subject of a destroyed totalitarian regime, when everything he knows about the world around him is a lie.

The 52nd Molodist has once again confirmed the ability of Ukrainian festival organizers not only to introduce the domestic audience to the most remarkable films of world cinema, but also to comprehend significant and uncomfortable topics through the art of cinema, and to resist the lies of propaganda fiction.

Oleksandr Husiev. Kyiv

First photo: molodist.com